Trading

Glimmers in the Shadows: Perception and Reality in Global Coloured Gemstone Trading

Introduction

In this paper we explore the ways in which coloured gemstones are traded. We pick up their journey as they leave the mine site and are passed hand-to-hand, crossing countries, continents and oceans, making their way to cutters, polishers, treaters and jewellery-makers around the world.

The coloured gemstone trade can be perceived very differently by different people along the supply chain. To some it might seem an arcane relic of a bygone era, hard to reconcile with modern notions of supply chain traceability and responsible sourcing assurance systems. To others, it is a fine edifice of traditions and practices honed over centuries – the lifeblood of the coloured gemstone world. We aim to show that while people in the supply chain may be divided in their perceptions, there is much in reality that unites them. Not least, a shared desire for a thriving, vibrant coloured gemstone sector, that minimises harm and brings genuine value to those involved in it.

Traditionally, coloured gemstone supply chains work largely on trust between parties. Often few paper records are kept, and deals are sealed with a shake of the hand. In the modern economy of e-money, bitcoin, contactless credit cards and smart contracts, the way that coloured gemstones are traded might seem out of date, but gemstones worth hundreds of millions of dollars are being bought and sold successfully in the same way today as they have been for centuries.

The trade’s shrouded structure might be viewed as an opportunity for bad practices but that is not why it is shaped the way that it is. The process of coloured gemstone trading is technically challenging. It generates livelihoods for a vast network of small enterprises and individual traders, many of whom bring enormous resilience, expertise, skill and passion to bear, satisfying market demand for a wide variety of coloured gemstones. Through the income they gain, independent traders around the world can benefit those close to them - supporting their families, funding their children’s education, and contributing to development in their countries and communities.

Although the way the bulk of the coloured gemstone trade is conducted is rooted in traditional practices, the modern world is starting to press up against it. New technologies, such as blockchain-based traceability software and nanoparticle marking of stones have the potential to shine a light on supply chains. Meanwhile, some large companies are entering the coloured gemstone sector and introducing new trading models. Customer and retailer expectations for gemstone traceability and for assurances of responsible sourcing are steadily rising.

By examining perceptions and realities in coloured gemstone trading, this paper demonstrates the need for modern expectations, technologies and market forces to be reconciled with traditional practices, to foster a truly inclusive and widely beneficial ecosystem of coloured gemstone trading.

Our White Papers are also available to download and read offline.

Please fill in your details to receive a download request.

Imagine a group of artisanal miners, working an alluvial deposit in a remote rural corner of Sri Lanka. They find a sapphire. To the untrained eye, it could be mistaken for an irregular glass pebble or coloured rock – a far cry from the beautiful stone that might eventually be set into a piece of jewellery.

For the miners, who do not have the means to travel far, and whose skills in gemstone assessment, valuation and price negotiation may be limited, it is worth what local traders will pay. Traders will travel to mine sites, often undertaking long journeys on poor roads, to look for well-priced “rough” – unworked gem material – that will turn a profit, after transport and other expenses have been covered. The miners may have little option but to sell the sapphire to this trader, probably someone already known to them and their fellow workers, for the price offered. Miners operating at this scale and in remote locations typically cannot afford to hold out for a better deal, which might well never come.

The trader then transports and sells the sapphire to the next person in the chain, often in the nearest town with good communications, where a cluster of buyers will congregate. This person could be another mobile trader or in an office, or a regular at a nearby gemstone market, such as Beruwala. Sometimes the rough will be sold directly to a lapidary who will pre-form, cut and polish it into a jewel for the domestic jewellery industry, or it will travel onwards to Colombo, Sri Lanka’s national and foremost international trading hub, changing hands several more times on the way to reach an international trader or buyer, where it is joined by thousands more sapphires from other parts of Sri Lanka and also from other countries.

Beruwala Gemstone Market, Sri Lanka –

where you can buy stones from all over the world.

Photo credit: TDI Sustainability

The gemstones in Colombo – as in other locations – are sold on their merits of colour, weight, and clarity. While there is no official pricing system, business is transacted within remarkably well-defined price ranges, known to local traders.

Traders sell for what they can, and this may be just the first of several hubs the gemstone travels through internationally. A stone will likely be cut, polished and probably treated at one of these hubs, if it wasn’t already, earlier in its journey.

Very small gemstones known as melee – less than 0.20 carats each in weight – tend to be sorted by size and quality and sold in parcels of specific weights. This provides a degree of predictability in their contents, and aggregates stones from all over the world. Larger, more unique and especially desirable gemstones – for example those suited to a solitaire ring, or a pair of earrings – will be sold individually or in matching pairs.

Buyers who come to these hubs might work for jewellery companies, or they could be independent traders in touch with designers, goldsmiths and retailers in their own country. They may be scouting for unique pieces, or they might have bulk orders to fulfil, stipulating the number of gemstones, their colour, clarity, cut and carat weight – probably their dimensions too – as well as, of course, the budget. In some cases, a stone’s origin, and any treatments it has undergone, may also be important to a buyer. For example, if a company has committed not to source from a specific place for ethical reasons or wants to be able to make claims about the stone being from a prestigious origin, or being unadulterated from its natural form.

Eventually, the sapphire in our story will be set into a piece of jewellery. If it is valuable then it might sit as the centre stone of a ring, with smaller sapphires on either side whose own journeys started in completely different parts of the world. The ring might be sold on to a wholesaler and then a retailer, or perhaps the manufacturer itself has a retail arm and a sales brand, or could be an independent designer-maker or goldsmith with their own shop window. From there, perhaps supported by marketing efforts and the sales expertise of staff on the shop floor, the ring will attract the attention of a customer, and find its way onto someone’s finger.

As a final twist to this tale, now imagine that all the events described above took place fifty years ago, or a hundred years ago, after which point the ring was treasured for many years by its owner. The owner eventually passes, and years later the ring finds its way onto the workbench of a jeweller, who prizes out its central stone with care, swapping it for a ruby for a client, and puts the sapphire up for sale. Its journey begins once again.

If the gemstone could speak then it could describe the people and places it encountered along its journey. Most jewellers and traders usually have a pretty good sense of from where rough originated, based on years of experience, but would find it hard to offer concrete assurances beyond those they receive from their long-standing business partners.

This typical story, therefore, highlights the challenges of applying modern notions of traceability to gemstones’ journeys and origins, and of establishing mechanisms to carry ethical assurances down the supply chain, in line with the customers’ and retailers’ rising expectations.

Over the course of this paper, we take a magnifying glass to the journey of coloured gemstones. Is the story above really typical? What other types of gemstone journeys are there? Who benefits along the way, and how, what innovations could break the status quo, and what does all this mean for responsible sourcing? We explore these issues in the sections to come.

Trading near mine sites

The miners who discovered the sapphire in our story worked in a small group, with basic tools such as picks and shovels. In responsible sourcing nomenclature they would fall under the category of artisanal and small-scale miners (“ASM”), and The World Bank estimates that 80% of sapphires globally are produced by such ASM groups1“Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining”. The World Bank. 21st November 2013. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining. Industry sources cite2“Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining”. The World Bank. 21st November 2013. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining similar percentages for other types of coloured gemstones too3“Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience”, p8. Natural Resource Governance Institute. May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/governing-the-gemstone_sector-lessons-from-global-experience.pdf. So the miners depicted in our story are quite typical (more information on how coloured gemstones are mined is given in another paper in this series: Hands that Dig, Hands that Feed: Lives Shaped by Coloured Gemstones Mining.

It is also typical for artisanal and small-scale miners to be removed, geographically, from gemstone markets. Many important sites for ASM gemstone mining are remote and under-developed. For example, the densely forested hills of Colombia’s Western Boyacá province, the dry, mountainous district of Badakhshan in the far north-eastern corner of Afghanistan, and the island of Madagascar, 400 miles off the coast of mainland Africa. Other sites may be closer to main roads and towns.

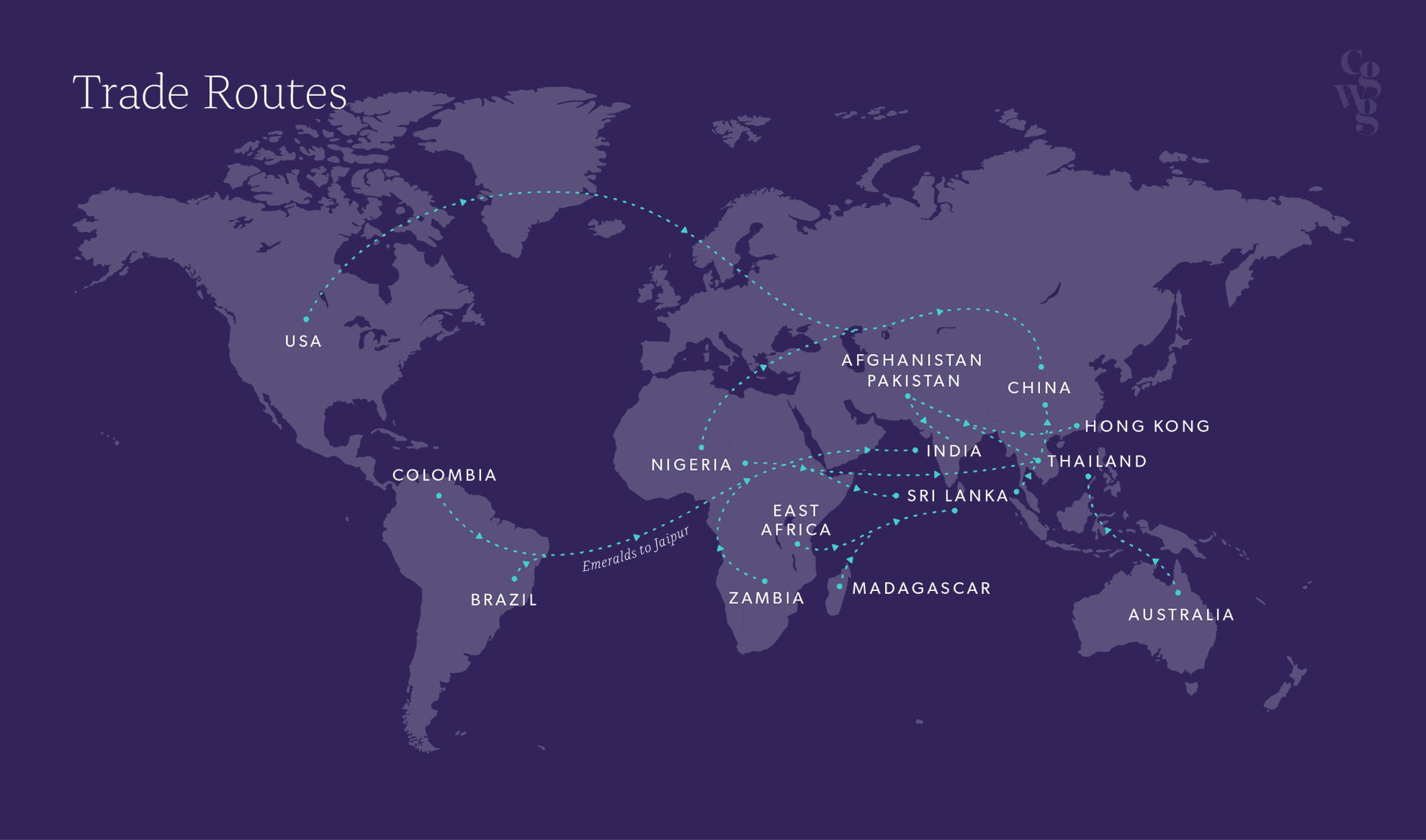

Miners working in these remote locations, many without ready access to transport or the means or contacts needed to sell far afield, will often sell to traders from towns and villages local to the mine who form links in a long chain, stretching over oceans, and criss-crossing countries and continents.

Much of the trading close to the mine will be informal, with little paperwork changing hands. Cash transactions are common, though mobile phone payment systems like M-PESA are fast gaining in popularity because they eliminate the risk of carrying hard currency.4“What is M-PESA?”. Vodafone. https://www.vodafone.com/about-vodafone/what-we-do/consumer-products-and-services/m-pesa

National and international trading

As illustrated, a gemstone may change hands several times after leaving the mine. The traders who operate in towns and villages near mine sites will typically sell gemstones to other traders, coming from larger towns and cities, and the stones will then likely pass through many trading hubs – some of which will be small local markets, and others of which will be vast international centres for gemstone exchange and processing 5“Rough Cut: Sustainability Issues in the Coloured Gemstone Industry”. SOMO. February 2010. https://www.somo.nl/app/uploads/2010/02/Rough-Cut.pdf. As gemstones travel through these hubs, they pass through facilities that sort, grade, cut, and polish them, and often treat them to improve their colour and clarity. Then, after leaving such hubs, gemstones pass through traders again to jewellery manufacturers and retailers before reaching an end customer6“Ibid.

Each transaction in the process is typically undertaken by small trading enterprises or individual traders. Sometimes, these traders will be guided by supply-side considerations – knowing what gemstones they can source, and for what cost, and trying to place these gemstones with buyers to turn a profit. At other times, these traders will be guided by demand. A buyer might place an order with a trader for a set quantity of a certain type of stone, and it will be up to the trader to engage with their network to have the order filled. If an order is particularly large or specialised, it can take years for a trader to fulfil it, effectively building up a new supply chain in the process, reaching up to the gemstone deposits themselves, often with no guarantee of a sale at the end.7Based on an interview conducted for this paper with Manraj Sidhu, Director at Multiple Gems Ltd, in December 2019.

Informality and the importance of trust

Each one of these traders, whether operating locally, nationally, or internationally, typically maintains a complex network of relationships – professional, personal and a mix of the two. Historically, the gemstone industry at all levels and scales has been predominantly based on trust, often relying on business relationships within and between families that span generations. There is often little paperwork associated with transactions, before stones are exported from their country of origin. At the point of export and after, customs declarations and written invoices may begin to appear.

In East Africa, in the present day, a ruby worth tens of thousands of dollars can change hands on a dirt street with no paperwork at all: given to a trusted expert who will examine it, work out the best way to cut it, perhaps pre-form it – creating the shape onto which facets will be placed – and then hand it back to its owner a week or so later on the same street, all based on trust.8Based on observations from TDI fieldwork in East Africa in October 2019.

Dealing with trusted partners helps gemstone traders to avoid financial losses, in the absence of a paper trail or reliable legal recourse, and to avoid disputes, suspicions and accusations. Trust and reputation are inextricably linked in the world of coloured gemstone trading, and traders who break trust once risk their reputation for life – without which they cannot work. Trust is maintained because traders know that the consequences of breaching trust outweigh any short-term benefits that they could hope to gain from doing so.

Dealing only with trusted partners in the gemstone trade is also about physical security for traders. Arranging official export paperwork and engaging a professional courier willing to ship gems can be onerous, time consuming and costly9TDI interview with international coloured gemstone supplier, June 2019. So, in practice, many gem dealers simply carry gems unofficially, and discreetly, about their person. This leaves them vulnerable to robbery, assault, and worse, and the risk is ever present – whether they are on the streets of London or in a Malagasy village.

A trader may have a network of trusted shops in the towns he visits that will let him store his gemstones in their safe overnight. A particularly rare or valuable gemstone might only be offered to trusted contacts, or people personally recommended by a trusted contact, lest its existence become known to too wide a circle of people. Close to the mine site, a foreign trader may choose to stay put in a hotel and have local ‘runners’ come to him with gemstones he might want to buy – relying on the runners’ own trust networks to keep them from harm.

Back, forth and around again

A gemstone’s journey may not be one straight line from mine to customer. Gemstones can be traded back and forth many times. An intermediary trader, for example, could present a parcel of gemstones, roughly sorted by size and colour, to a buyer, who then selects the gemstones they want and returns the surplus to the same trader, or passes them on to another trader entirely.

It is rare that a gemstone will only have one final owner. Gemstones are imperishable, and they concentrate considerable value in a small size and weight. After decades of use, or speculative storage, a gemstone can simply be put back on the market again. According to an estimate by coloured gemstone experts Laurent Cartier and Vincent Pardieu, in a blog published by National Geographic “fewer than 2% of gemstones in circulation were mined in the last two years.”10“Conservation Gemstones: Beyond Fair Trade?”. National Geographic Society Newsroom. 17th October 2017. https://www.sustainablegemstones.org/research-library/2017/10/17/conservation-gemstones-beyond-fair-trade

Important gemstones are also passed down through generations as heirlooms, often to be resold on the open market when a family’s circumstances change. Or they may be held for more commercial reasons, by speculators who wait until the price of a particular type of stone is high enough to realise a good return on their investment11“Sapphire Shop”, Case Study No. 32 of the Lubin Business School Case Studies series. Pace University. 17th April 2007. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/business_cases/6. Coloured gemstones can re-enter the market at a number of stages – perhaps through an auction house specialising in fine vintage jewellery for collectors and high-end retail customers, or maybe via an intermediary trader who adds value to the stone by cutting, polishing and perhaps treating it again, either to repair damage from wear, or to keep up with changing market preferences. Many coloured gemstones continue to be bought and resold long after the mine that they came from has closed and faded into memory.

Large-scale miners as traders

In recent years, large mining companies including Belmont, Gemfields, The Muzo Companies and Greenland Ruby have established themselves in the coloured gemstone sector. Unlike small, traditional gemstone miners, these companies operate over large concession areas and, in the case of Gemfields, in several countries (the topic of large-scale gemstone mining is covered in the paper in this series Hands that Dig, Hands that Feed: Lives Shaped by Coloured Gemstone Mining.

Each of these companies have set up trading arms within their business structures. This reduces their need for intermediary traders and ultimately shortens supply chains. Gemfields’s trading operations in particular are highly developed, and involve grading of rough gemstones and formal, structured auctions for traders.

Gemfields also undertakes marketing efforts to end customers, and collaborates with designers, including through their in-house brand Fabergé, to showcase their stones in jewellery that can be purchased through their website12“Collaborations”. Gemfields website. https://gemfields.com/marketing-sales/collaborations/. Through marketing campaigns, vertically integrated companies can increase demand for their stones in ways that miners who do not vertically integrate cannot hope to replicate.

The Colombian emerald mining company Muzo adopts a similar approach to Gemfields, with an online store and physical shops in New York and Geneva, through which it sells a range of high-end jewellery featuring the stones that it mines. It also issues certificates of origin to accompany its stones, allowing traceability up to the specific shaft or tunnel where each was produced. Greenland Ruby, too, keeps its supply chain fully traceable, by selling exclusively to ‘preferred partners’ for cutting, polishing and distribution, who ensure that each stone carries with it a certificate of origin issued by the Greenlandic government13“Responsible Source”. Greenland Ruby website. https://www.greenlandruby.gl/responsible-source/.

These large companies can offer things to buyers that small scale traders generally cannot: consistency and transparency of supply. A large-scale mining company can be confident that it will produce roughly the same volume of stones, with roughly the same distribution of sizes and qualities, month on month for several years. A jewellery-maker who sources his or her stones from a large mining company can be assured of a steady stream of similar stones with which to work. Also, he or she can also know the history of these stones and reassure customers regarding their origin.

Currently, large-scale mining only accounts for about 20%-30% of non-jade coloured gemstone production14Extrapolated from: “Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining”. The World Bank. 21st November 2013. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining, and is restricted to high-value stones such as rubies and emeralds. Growth potential for large -scale mining is limited, since large mines rely on large gemstone deposits with enough valuable stones to ensure commercial viability. There are very few such deposits in the world, and each deposit produces a narrow range of stone types. Yet jewellers and their customers want a great variety of coloured gemstones. This means that large-scale mining will not come to replace small-scale gemstone production, as industrial companies have overtaken artisans in so many other supply chains worldwide.

Nonetheless, many traditional gemstone traders are apprehensive of these newcomers15This section is based on several interviews conducted by TDI with experts from large gemstone companies and from the world of small-scale gemstone trading.. One concern that small traders articulate is that the allure of a consistent, dependable product will tempt buyers away from the diverse, rich and unpredictable stock they can offer, irrespective of whatever skill and expertise they pour into selecting their gemstones. Another concern for small traders is that the supply chain traceability and assurances that large companies can offer will increasingly come to be expected by their own clients – expectations they may not be able to meet.

As with any market disruption, the advent of large coloured gemstone companies creates challenges for traditional participants in the sector, which they must face in order to remain competitive.

Many traders would point to the advantages that traditional trading models can bring. For example, the director of a small, family-owned trading company in Tanzania, Manraj Sidhu, gave his opinion for this report:

“When you buy from a local trader in a gemstone-producing country, all the money you part with flows into the local economy in one way or another. For a country to benefit from its gemstones, the maximum fraction of the value of those gemstones should stay in the country – these gemstones start as dust in the ground, and you’re literally turning them into dollars. Large mines might pay 30%-40% of their revenues in taxes, but most of the remaining 60%-70% leaves the country, so small traders can help to retain more value for producer countries."16Interview with Manraj Sidhu conducted in December 2019

~ Manraj Sidhu

Supply chain shortening in the information age

In many economic sectors the advent of the internet has brought about the shortening of supply chains. In the modern age, household items can be ordered directly from sellers with close ties to manufacturers, in China or elsewhere, without the involvement of networks of international importers and distributors. Holiday packages, likewise, can be bought straight from aggregator websites, reducing the need for travel agents.

These trends are present in the coloured gemstone sector, just as they are for other goods and services. Gemstone traders in producer countries have in some cases begun to advertise stones on their own websites for sale direct to jewellery-makers or end customers17See, for example, the website of the Ceylon Gem Hub: https://ceylongemhub.com/. Online stores such as eBay offer coloured gemstones in abundance and can give steep discounts on high street prices – though some users of such sites express deep reservations about the authenticity of the stones offered for sale18“Are all or most of the imported gemstones sold on Ebay fake?”, Ebay discussion forum, accessed 21st October 2021. https://community.ebay.com/t5/Archive-Fine-Jewelry-Gems/Are-all-or-most-of-the-imported-gemstones-sold-on-Ebay-fake/td-p/1378535.

The trust issues that exist over ad hoc transactions with semi-anonymous traders, in uncontrolled environments, are one factor that gives impetus to the development of dedicated online gemstone trading platforms, on which traders can be screened, monitored, and sanctioned for misconduct where necessary. One of the most recent of such platforms is GemCloud, an inventory management system that allows detailed stock information to be synched to its global online marketplace19“The Software for Color Gemstones You Can Trust”. GemCloud website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.thegemcloud.com/. The system was launched in March 2020 by a group of experts in coloured gemstone trading and gemmology. It is designed to accommodate gemstone-specific sales mechanisms such as memo transactions and can allow traders to quickly search for stones or parcels for sale that match their requirements, irrespective of physical distance20“The Software for Color Gemstones You Can Trust”. GemCloud website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.thegemcloud.com/.

GemCloud’s CEO, Mariaveronica Favoroso, shared her perspective on the potential benefits of the platform for the coloured gemstone trade in an interview for this paper:

“One of GemCloud’s most compelling features is its potential to empower small-scale traders. It can be used by traders in mining regions in Africa, Asia or South America to connect directly to buyers without the need for long chains of middle-men or international travel. GemCloud is an evolution of the traditional, interpersonal, trust-based model of gemstone trading, which had already started to shift in recent years. Pre-coronavirus, traders who could afford to travel sold outside their trust circle at gem shows in Tucson, Hong Kong, and elsewhere. GemCloud makes virtual gemstone trading available to all. Many traders are selling online already, but they’re doing it with pictures of stones sent on WhatsApp. With GemCloud they can trade in a standardised digital environment, which we believe is safer and more transparent. Traders are encouraged to join the Gemstones and Jewellery Community Platform, to enable them to get up to speed with basic environmental, social and governance good practices. A carefully curated marketplace like this is the only way to truly evolve from the close, personal, ‘handshake’ way of trading gemstones.”

Another new platform, Singapore-based Gembridge, provides online showcasing and trading of certified coloured gemstones for a verified community of buyers, sellers and consignees. Like GemCloud, it is designed to extend the reassurance of dealing face-to-face with a known, trusted counterparty to a virtual environment.

Gembridge acts as an intermediary in sales transactions, collecting payment from buyers and only releasing it to sellers once gemstones have been delivered and signed-for. 'Gembridge Hubs' are located in several key coloured gemstone trading cities worldwide, to which gemstones sellers can ship items for verification, before they are forwarded on to buyers. Consignment, escrow and secure physical viewing services can also be arranged through Gembridge upon request 21“How it works", Gembridge website. Accessed 26st October 2021.

Which gemstones flow where?

Within most countries that mine coloured gemstones there is a body of craftspeople who can cut, polish and treat these stones for the local market. However, countries without a long tradition of gemstone mining (particularly in Africa) often lack the know-how to cut, polish and treat gemstones to the standard required by international buyers. In such cases, gemstones are typically exported rough to other countries with more established processing industries.

Trading destinations for these gemstones are often determined by proximity. East African gemstones, for example, are frequently exported to Colombo, Sri Lanka – a nearby gemstone hub, across the Indian Ocean. They are then cut and polished, and often treated, and traded on from there.

Trading destinations can also depend on the type of stone being traded, because Certain hubs are known for their cutting and polishing expertise for specific types of gemstone. Emeralds from Zambia, for example, are more likely to end up in Jaipur, India, than they are to be traded through Sri Lanka, because Jaipur is an important trading and processing hub for emeralds. Despite the fact that emeralds have never been mined in India, Jaipur has specialised in the cutting and polishing of these stones ever since the 1700s when the Raja of Amer invited craftsmen to come to the city to make it a leading centre of luxury jewellery22“Jaipur, India: The Emerald Cutting and Trading Powerhouse”. GIA Field Report. 8th February 2016. https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research/jaipur-india-emerald-cutting-trading-powerhouse23“Romancing the Stone”. Business Today. 25th December 2011. https://www.businesstoday.in/magazine/reporters-diary/jaipur-emeralds-business-global-polishing-centre/story/20734.html. As well as receiving the majority of Zambia’s emeralds, Jaipur also takes the majority of rough emeralds from Brazil.

In some cases, the trading destination depends on the size and quality of the stone. Some trading hubs specialise in high quality single stones, while others focus on the trade of melee - smaller stones that are sorted, cut, often treated, and finished to be uniform in shape and size. Sri Lanka, for example, takes high-quality sapphires from around the world – not just from East Africa. It is renowned for the precision cutting skills of its craftspeople, which have been passed down and honed over the centuries that Sri Lanka has mined its own sapphires.

The city of Chanthaburi in Thailand, on the other hand, has become the biggest centre in the world for processing high volume, lower-grade sapphires, rubies and other stones. In contrast to Sri Lanka, Thailand’s pre-eminence for gemstone processing only came about after the country’s domestic sources of high-quality gemstones began to dry up, in the mid-twentieth century. Faced with declines in gemstone quality, Thai craftspeople adopted and refined heat treatment, filling and other improvement techniques to enhance the colour and clarity of lower quality gemstones, and traders then began to move gemstones from other countries through Thailand too, so that they could enhance their value through these techniques24“A market like you've never sheen”. The Hindu. 29th July 2017. https://www.thehindu.com/thread/arts-culture-society/a-market-like-youve-never-sheen/article19384978.ece.

The town of Idar-Oberstein in southwest Germany caters for gemstones at the other end of the spectrum – crafting rare and high-value jewels for the luxury market. Nestled in the Hunsrück Mountains, this historical town was an important source of agate, jasper and quartz for many centuries. Like Chanthaburi in Thailand, the city of Idar-Oberstein has lived on as a hub for the processing of coloured gemstones, even though its own deposits are now largely exhausted. Traders in the city import rough gemstones from all over the world, to be cut and polished by the city’s master craftspeople. Although the quantity of gemstones that moves through Idar-Oberstein is far lower than the amounts processed in Sri Lanka and Thailand, this quiet Rhineland town enjoys a towering reputation for quality in the world of gemstones and jewellery25“Lapidary Tradition of Idar-Oberstein”. James Shigley, Gemological Institute of America. 2019.

https://www.gia.edu/UK-EN/lapidary-tradition-idar-oberstein-reading-list.

Global trading patterns in coloured gemstones are shaped by the fact that expertise has inertia. Highly specific skills and techniques, that have been honed over decades, if not generations, cannot easily be transplanted to new countries and new contexts, or to novel types of stones from unfamiliar deposits. As well as shaping the nature of gemstone trading, this fact has very significant implications for “value retention” initiatives, which aim to foster processing industries in under-developed gemstone producing countries. We explore this issue in depth in the next paper in this series, Wheels of Fortune: The Industrious World of Coloured Gemstone Cutting and Polishing.

‘Responsible sourcing’ is a term used for an approach to supply chain engagement that seeks to maximise benefits for material producers and processors, while mitigating any negative environmental, social and governance impacts that are associated with the materials that are being supplied. Responsible sourcing is advocated for by a cadre of international bodies and civil society organisations, and its implementation can take many forms, but it invariably entails detailed knowledge of supply chain structures. Without this knowledge, it would be difficult to target improvement and mitigation efforts effectively.

When looking at a jewel in a shop window, it is unlikely that you will be able to determine with confidence which country it came from, let alone which mine, and it is all but impossible to learn who benefitted along its journey. These difficulties in traceability present a significant challenge for the objectives of responsible sourcing, as do other aspects of the coloured gemstone trade, including challenges associated with fair valuation, gemstones’ vulnerability to smuggling, and instances of association with illicit financial flows and conflict. We examine these challenges to responsible sourcing in the following section.

1. Valuation of gemstones

An artisanal miner extracting gold, tin, tantalum or other mineral ores generally has a good idea of how much the materials he mines are worth. In the case of gold, even small-scale miners generally have means to access to the London gold price - it can be passed along by mobile phone, and some gold refiners offer to send this information via SMS as a free service. It is also often displayed publicly in mining settlements. by comparison, each gemstone is unique and requires expertise to value. There is no common standard against which gemstones can be appraised, and ultimately their only true value is the amount that a buyer is prepared to pay. This means that if one party to a trade has less expert knowledge than the other then they are vulnerable to being misled. The knowledgeable party can undervalue the stones they buy from miners and others, or overvalue stones they sell to other traders, cutters, polishers, jewellery-makers or customers on the high street.26Interview conducted in December, 2019.

To better understand the difficulties that gemstone valuation presents, one must first understand how coloured gems are valued.

How coloured gemstones are valued

A coloured gemstone’s value depends on its carat weight, its clarity and colour, the quality of its cut, and what treatments it has undergone.

A trader dealing in rough gemstones, which have not yet passed through the hands of the craftspeople who will transform them into jewels, can only speculate as to the value locked within them. A rough gemstone can look as unremarkable as a cloudy pebble, and great skill is required to discern what quality of jewel it could eventually become. Even professional gemmologists’ estimates of a rough stone’s value can vary by up to 30%27“Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience”, p46. Natural Resource Governance Institute. 22nd May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/analysis-tools/publications/governing-gemstone-sector-lessons-global-experience .

Once a gemstone has been cut, polished and treated, the properties that determine its value are no longer a matter of speculation and conjecture. They are measurable and they can be compared to data gathered from the sale of similar stones to benchmark its price (for example by using the GemePrice online valuation platform) 28Accessible at: https://www.gemewizard.com/gemeprice/.

Even for a finished gemstone, however, gathering this data is far from straightforward, and it still involves a degree of subjectivity. A gemstone’s carat weight can be measured using a relatively inexpensive set of scales, but its colour, clarity and treatment history require expert analysis, judgement and experience.

A gemstone’s colour is not just about hue (red, blue, green, and so forth). Saturation - the intensity of the colour - also plays a role, as does tone, which measures lightness and darkness29“Judging Quality: The Four C’s”. Pala International website. Accessed 21st October 2021. http://www.palagems.com/quality-4cs. All these properties must be assessed to gauge a gemstone’s colour, and there are no hard and fast rules regarding colour grades. For example, the mineral beryl sometimes occurs in a particularly verdant hue of green and is known as ‘emerald,’ but experts in gemmological laboratories often disagree over which stones can be considered emeralds and which are simply green beryl30“Emerald Description”. GIA website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.gia.edu/emerald-description. Likewise, both rubies and sapphires have the same mineral composition, known as corundum, but while sapphires can be blue, pink, orange or other colours, only corundum that is predominantly red can be designated and sold as ‘ruby.’

Even within a designation such as ruby, sapphire or emerald, not all colours are equal. Certain grades of colour attract special names, and higher price tags. Deep red rubies, which are most commonly associated with the Mogok Stone Tract in Myanmar, are known as ‘pigeon’s blood’ rubies and are highly sought after31“The Making of an International Color Standard by GRS: "Pigeon's Blood" And "Royal Blue". GRS Laboratory. Accessed 21st October 2021. http://www.pigeonsblood.com/s/The-Making-of-a-Brand-GRS-Type-Pigeons-Blood-May2015.pdf. Similarly, the most prized blue sapphires are of a particular colour known as “cornflower”, most commonly associated with production in Kashmir32“What exactly is the Cornflower Blue Sapphire”, Gemstone Universe website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.gemstoneuniverse.com/what-exactly-is-cornflower-blue-sapphire.php(for more information on the distribution, geology and chemistry of different types of coloured gemstone, see the paper in this series, Hands that Dig, Hands that Feed: Lives Shaped by Coloured Gemstones Mining).

Gemstone colour grades are predominantly assessed by eye. A stone’s treatment history, on the other hand, is often indiscernible to the naked eye. Its discovery requires the use of specialist equipment and technical expertise outside the reach of most coloured-gemstone traders.

Nonetheless, a stone’s treatment history is closely tied to its perceived prestige, and it can have an enormous impact on a gemstone’s value. An untreated one carat ruby, for example, can sell for ten times the price of a visually-similar treated ruby 33Estimate by Matthias Krismer, procurement manager at Swarovski..

Tools, standards and initiatives to help with valuation

Classification

Common terms like ruby, sapphire, amethyst and citrine are formalised by international bodies including CIBJO, which is the French acronym for the Confédération Internationale de la Bijouterie, Joaillerie, Orfèvrerie des Diamants, Perles et Pierres (which translates as the International Confederation of Jewellery, Silverware, Diamonds, Pearls and Stones, and is also referred to in English as the World Jewellery Confederation). CIBJO defines acceptable terminology throughout the world for the jewellery industry, including for coloured gemstones. The CIBJO Gemstone ‘Blue Book’ sets guidelines for how gemstones should be classified and traded to promote clarity and honesty34The CIBJO Blue Books are available here: http://www.cibjo.org/introduction-to-the-blue-books/. The guidelines must be followed by all traders who are affiliated with CIBJO globally.

A key element of CIBJO’s work is the harmonisation of standards, and the promotion of responsible business practices through jewellery industry supply chains. To support the latter, in June 2021, it launched a responsible sourcing toolkit which is provided at no cost to all participants in the supply chain worldwide35“CIBJO Responsible Sourcing Tool-kit.” CIBJO, June 2021. http://www.cibjo.org/rs-toolkit/. The CIBJO toolkit is also hosted on the Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform, a free online source for a rich array of sustainability tools developed by the Coloured Gemstone Working Group for all sizes of businesses in the supply chain and currently used by hundreds of suppliers to major jewellery brands36The Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform is available here: https://www.gemstones-and-jewellery.com/.

Disclosure

The CIBJO Gemstone Blue Book calls for sellers of gemstones to fully disclose information about the nature of the gemstones they are selling at the time of the sale, regardless of whether the buyer has requested the information or not. This information includes the type of stone it is and any processes and treatments that it has undergone (which we discuss in the next paper in this series, Wheels of Fortune: The Industrious World of Coloured Gemstone Cutting and Polishing). The guidelines go on to stipulate how certain terms can or can’t be used, including ‘real’, ‘precious’ ‘genuine’ and ‘natural’. Disclosure must be made verbally, and also in writing on all commercial documents relevant to the sale. This protects all industry participants and builds consumer confidence in the jewellery trade.

Most countries have trading standards for gemstones too. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission, for example, provides a guide for the jewellery, precious metals, pewter, diamond, pearl and coloured-gemstone industries, which for gemstones details how words relating to physical characteristics such as colour, weight and cut can or cannot be used to sell them, as well as giving details of what needs to be disclosed37“Electronic Code of Federal Regulations, Part 23. Guides For The Jewelry, Precious Metals, And Pewter Industries”. US Government website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=1&SID=4a2f3f01fd9b6bfd85de4de12e987c2f&ty=HTML&h=L&mc=true&r=PART&n=pt16.1.23.

Gemmological laboratories

Gemmological laboratories assess and attest to all the physical characteristics of a gemstone that influence its value: its carat weight, its clarity and colour, species, variety, its exact dimensions, whether it is natural or synthetic and any treatment or enhancement it has undergone38Sample coloured gemstone origin report from Gemmological Institute of America. https://www.gia.edu/analysis-grading-sample-report-colored-stone.

In addition, they assess – where requested and possible – gemstones’ country of origin which, for some stones, such as emeralds, rubies and sapphires, can play an important role in determining their value.

Gemmological laboratories attempt to establish gemstone origin using a range of equipment to compare mineral composition and physical properties against reference samples collected at mines or submitted from them. Laboratories offer this service, usually reserved for valuable gemstones, to corroborate claims made by gemstone sellers and assure buyers over the transaction. Ultimately, however, a laboratory’s origin report is an opinion, made subjectively based on similarities with the stones in that laboratory’s reference collection. Depending on the varying qualities of different reference collections, it is possible that two laboratories will disagree regarding a stone’s inferred origin. Also, each time a new deposit is discovered and exploited in the world, gemstone laboratories will be challenged to correctly identify the stones that come from it, until such time as they have acquired sample stones for their own collections.

The cost of an origin report typically starts at around US$ 70, plus transportation costs for the stone to get to the laboratory and back. So, while an origin report can be a traceability solution for larger and more valuable stones, it is generally not commercially viable for smaller and cheaper stones, particularly outside the ‘big three’ of ruby, emerald and sapphire39The GIA price list, for example, is accessible here: https://www.gia.edu/doc/Lab_FeeSchedule_ColorStone_EN_USD_2021_1001.pdf.

Education

Miners are often less knowledgeable about gemmology than the traders they sell to, and this can put them at a disadvantage. The difference between a deep pink or reddish-orange sapphire and a red ruby, for example, can be incredibly subtle, and all but impossible to distinguish to the untrained eye – they are only slight chemical variants of the same mineral, after all. Yet a ruby is considerably more valuable than a sapphire of comparable size and quality.

Improved gemmological and market knowledge enhance miners’ capabilities in negotiations and trade relationships. There are a growing number of initiatives working around the world to equip gemstone miners and their communities with field gemmology and gemstone valuation skills, to help them to lay claim to more of the value of the gemstones they mine.

To give one example, in 2017 the GIA (the Gemmological Institute of America) developed a guide to rough gemstones that artisanal miners in Tanzania can use to help sort their mined material and better understand its quality and value40More information on the project is available here: “GIA Develops Free Gem Guide for Artisanal Miners”. GIA press release. 4th April 2017. https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-press/gem-guide-artisanal-miners. The program has since been expanded to other areas of Tanzania.

Another example is an initiative funded by GIZ (the German development agency) and then latterly by Tiffany & Co, to provide free, basic field gemmology tools and training to women involved in the sapphire supply chain in the gem-producing regions around the towns of Sakaraha and Ilakaka in Madagascar. This training aims to equip female traders with sufficient knowledge to achieve a fair price for the stones that they sort and sell41“Signature Project 2 - Gemmology and Lapidary for Women in South West Madagascar”, Gemstone and Sustainable Development Knowledge Hub website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.sustainablegemstones.org/signature-projects/signature-project-2.

Photo: A female miner working with sapphire melee in the Women’s Lapidary Centre in Sakaraha, Madagascar, Lynda Lawson.

Some upshots of variable valuation

Despite the tools, standards and initiatives described above coloured gemstone valuation remains challenging, and dependent on specialist knowledge.

The difficulties of gemstone valuation are a significant hurdle for effective taxation42“What’s sexier than gemstone taxation policies?”. Myanmar Times. 13th October 2014. https://www.mmtimes.com/business/11928-what-is-sexier-than-revising-gemstone-taxation-policies.html(alongside instances of smuggling, which are discussed below). Imagine a hypothetical trader in a gemstone-producing country and a counterpart in an international trading hub, who have built up a trusting relationship over many years. The two traders might make a deal over a string of messages on WhatsApp and fix a price between them for a parcel of gemstones. An idea might present itself – to write down one tenth of that price on the export paperwork. The customs official who inspects the gems, and levies border taxes, likely has no knowledge of gemmology, hue, tone, or other technical factors, and would be in no position to disagree with the claimed value of the stones. If they chose to do this, the customs collector would lose out, and so would the social, healthcare, infrastructure and development projects that that revenue could otherwise support.

Variable pricing can also exacerbate power imbalances between supply chain participants. An anecdote from Manraj Sidhu, the director of a small Tanzania-based trading company, illustrates this issue:

African traders travel to Bangkok quite frequently to try to sell parcels of stones there, but sometimes they will be offered very poor prices. A stone that could fetch US$ 150 in a fair market might receive offers of a fraction of that price. After a few days in Bangkok, with hotel bills racking up, the African traders will cut their losses and sell for whatever price they can get, and a few Bangkok traders know that and capitalise on it43Interview conducted in December, 2019..

The challenges of gemstone valuation also present difficulties for responsible sourcing movements such as “fair trade”, which rely on giving producers a greater share of a product’s final market value. If that final market value cannot be reliably predicted, then a ‘fair’ proportion of that value can obviously not be paid. There are workarounds to this issue, of course, but as in any industry a workaround increases complexity, and complexity increases overhead costs.

2. Traceability of gemstones

Keeping ahead of the competition

The gemstone market is highly segmented, built on individual traders’ knowledge and expertise regarding particular stones. It’s also very fluid, with market demands shifting regularly to follow changing fashions and trends.

Traders therefore depend greatly on their close network of business alliances to stay ahead of who buys what, how they value the pieces that they buy, and what they are prepared to pay.

Fundamentally, a trader – like any businessperson – is always looking for a good deal. When a trader finds a source of gemstones that presents a new and strong commercial opportunity, they will be inclined to keep the source confidential. Their commercial interest lies in keeping competitors away from the miners, or other traders, from whom they buy the stones. And they will want to find a good buyer for the stones, in turn, and keep that buyer confidential too. If their suppliers think that the traders are not selling their stones on for the best price, or that other traders can access the same buyers with less markup, then they may well choose to drop the original partner for their competitors. Embracing full transparency can be a precarious prospect for small-scale coloured gemstone traders.

The challenges of traceability

Reacting to the responsible sourcing movement, retail companies in many industries are increasingly asking suppliers for accounts of where the materials in their products have come from, how they have been produced, how they have been transacted, and the ethical circumstances of their journeys (as discussed in the paper in this series A Storied Jewel: Responsible Sourcing and the Coloured Gemstone Retail Sector).

Achieving traceability in coloured gemstone supply chains is uniquely challenging, however. As noted above, the coloured gemstone trade is largely informal and trust-based, with few records kept of transactions. Traders in gemstone producing countries will often have a good idea of the geographical area which their stones come from, based on the information given to them by their suppliers and the physical properties of the gemstones themselves. This information may be passed on to international buyers, particularly those who visit in person and who make it their business to find out. At international trading hubs, however, the situation is different. Gemstones can be grouped with stones from completely different parts of the world, un-grouped in a subsequent transaction, and grouped again in different ways after that, before finally reaching an end customer.

Many within the industry will argue that complex trading webs are a natural reflection of gemstones’ fundamental nature. Gold mined in Ethiopia is the same as gold mined in the United States, so there is no need to ship specific pieces of gold around the world to meet individual customers’ needs. This is not true of gemstones, since there are so many types, since each individual stone is unique, and since precise combinations of stones are often required to produce the aesthetic effect that a jewellery-maker wants to create.

When gemstones pass through the hands of many experts, each of whom has thorough knowledge of the skills and specialisations of the next expert in the chain, these stones can be guided to the cutters, polishers and treaters best able to bring out their individual appeal, and to the jewellery-makers best able to set them into pieces that suit them and the market. From complexity, beauty can arise.

There are other reasons, too, for trading chains to stay complex. Consider the archetypal foreign trader, discussed above, who visits a gemstone area and stays in his hotel, sending runners to bring him parcels of gemstones. Local traders closer to mine sites may guard their ‘turf’ zealously, since their livelihoods depend on exclusive access to their sources of stones. Other traders perceived as outsiders risk meeting resistance and even harm if they encroach. Thus, a multi-layered trading system is held in place.

Gemstone trading also involves complex inventory and sales mechanisms, which can vary widely across the supply chain. For example, the gemstone trade commonly uses a system of ‘memo transactions’44For more information on the subject see “The Essential Guide to

‘Memo’ Transactions”. The Jewelers Vigilance Committee and JBT. January 2009. http://jvclegal.org/app/uploads/2019/02/Essential_Guide_to_Memo_Transactions-2.pdf whereby gemstones are lent to others, so that they can be appraised and, it is hoped, sold on by the recipient. They are returned to the original owner if a buyer cannot be found.

In addition to these issues of complexity, gemstone supply chains can present opportunities for fraud and the substitution of stones, from the mine site onward. An anecdote from the field gemmologist Vincent Pardieu illustrates one method by which assured supply chains could be compromised by stones from non-assured sources:

“There was a recent case of a responsible sourcing initiative at a gemstone mine in Sri Lanka. The international partner seemed to put a lot of work into getting all the right systems in place for environmental and social protections, and they eventually had everything up-and-running, but the mine started to cheat the system. They brought in cheap, heat-treated gemstones from Madagascar, claimed they mined them themselves, to try to sell them at a premium as responsibly sourced Sri Lankan gems.”45Interview with Vincent Pardieu conducted in July 2019.

In light of the many challenges to the traceability of coloured gemstones that are outlined above, new technologies are being applied to the sector in the search for solutions. The most prominent of these - blockchain-based traceability and nanoparticle systems - were originally developed for other purposes and are being adapted to the gemstone sector. We examine both of these technologies in the next section.

The relationship between traceability and responsible sourcing is a complex one. We explore some of the ethical considerations around traceability at the consumer level in the paper A Storied Jewel: Responsible Sourcing and the Coloured Gemstone Retail Sector. In the paper Letting it Shine: Governance in Coloured Gemstone Supply Chains, we look at how traceability schemes (and responsible sourcing schemes generally) can create barriers to market access for small producers, and we discuss how traceability expectations might nonetheless be satisfied in future in ways that align with the commercial reality of coloured gemstone trading.

Blockchain-based traceability

Blockchain is an internet-based system for recording transactions, time-stamping them and encrypting them in a way that is tamper-proof and incorruptible. It is a “distributed ledger” technology, which means that there is no centralised storage of data. Information can be spread across multiple servers, in multiple countries or institutions, rather than being controlled by a sole administrator, which makes blockchain a very secure means of storing and protecting data. It is used, among other things, for cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

Blockchain can be used to document a gemstone’s journey from mine to customer and to verify changes in ownership, value and other relevant characteristics along the way, creating a tamper-proof historical record.

Blockchain-based traceability solutions currently face a number of practical barriers to effective implementation for coloured gemstones. Firstly, while the blockchain ledger itself is tamper-proof, it provides no assurance that the information entered into it is accurate. Also, the costs involved in blockchain are currently prohibitively high for use with everyday gemstones46“Is It Really Possible to Know Where Your Jewelry Comes From?”. JCK Online. 16th August 2019. https://www.jckonline.com/editorial-article/possible-know-jewelry-comes-from/ and, without integrated schemes for environmental, social and governance standards, a blockchain system provides no assurances on ethical issues. As the authors of an influential 2018 paper on blockchain in the gemstone industry put it, “the blockchain is only as strong as the data supplied,” and it “does not replace robust standards in the supply chain”47"Blockchain, Chain of Custody and Trace Elements: An Overview of Tracking and Traceability Opportunities in the Gem Industry", p222. Laurent E. Cartier, Saleem H. Ali and Michael S. Krzemnicki, The Journal of Gemmology, 36(3). January 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327555908_Blockchain_Chain_of_Custody_and_Trace_Elements_An_Overview_of_Tracking_and_Traceability_Opportunities_in_the_Gem_Industry.

Many experts who deal with blockchain-based traceability are enthusiastic about its potential and believe that solutions will be found to current challenges before long; costs will come down as the technology matures, and the appeal for younger-generation customers of accessing a wealth of data from mine to market will drive uptake and refinement of the technology48Based on insight from interviews conducted by TDI Sustainability with blockchain experts for this paper.. Traceability expectations from agencies such the FBI and Interpol may also drive future uptake of blockchain-based traceability. Whether or not its usage becomes widespread in the coloured gemstone sector, however, remains to be seen.

Since 2017, blockchain technology is being trialled in the diamond supply chain, pioneered by digital transparency company Everledger, the Diamond Time-Lapse initiative49“Diamond Time-Lapse: A Diamond Provenance Journey”. Diamond Time-Lapse website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.mydtl.io/#mining, tracks the journey of a diamond through every step in the supply chain and provides data about country of origin. Further initiatives have been launched by DeBeers50Tracr website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.tracr.com and IBM in partnership with diamond and jewellery companies51“The TrustChain Initiative”. TrustChain website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.trustchainjewelry.com.

For coloured gemstones, the Provenance Proof initiative, led by Gübelin Gem Lab in partnership with Everledger52“Provenance Proof”. Gübelin Gem Lab website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.gubelingemlab.com/en/provenanceproof, aims to provide data assurance issues by combining blockchain with an additional technology, the Emerald Paternity Test, which allows emerald rough to be marked at mining location using nanoparticle technology.

Nanoparticle systems

The ‘Emerald Paternity Test’53“The Emerald Paternity Test”. Gübelin Gem Lab website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.provenanceproof.com/emerald-paternity-test is a new nanoparticle technology developed jointly by The Gübelin Lab and Gemfields Ltd, that can establish the mine from which an emerald originated. It does this by applying synthetic DNA-based nanoparticles to rough emeralds at source, which can be decoded at any stage of the stone’s journey from mine to customer. The nanoparticles are not altered or damaged by any process applied to the stone, which ensures their permanence as an origin ‘marker’ even once cut and polished. The nanoparticles are invisible and do not affect the appearance or aesthetic quality of the stone at all. The natural imperfections within the crystal structure of emerald make it an ideal stone with which to pilot this technology, but those behind the project will try to find ways to apply it to other gemstones too, if it proves successful with emeralds.

The Paternity Test – like the Provenance Proof Platform itself – requires all users of the technology to abide by a Code of Conduct54“Code of Conduct for Users of the Emerald Paternity Test”. Gübelin Gem Lab. June 2018. https://www.provenanceproof.com/code-of-conduct-blockchain which demands adherence to applicable local and national laws, and requires that due diligence systems are in place to assure the gemstones are “mined or sourced legally, not in association with smuggling or supporting illegal activities55Ibid..”

The Code of Conduct further requires that “each authorised user shall define or select some basic ethical, social and environmental standards for all its operations, practices and processes that directly or indirectly relate to Provenance Proof technology or its processes56“Code of Conduct for the Provenance Proof Blockchain.” Gübelin Gem Lab. https://www.provenanceproof.com/code-of-conduct-blockchain.”

Provided that users observe this code of conduct, the Paternity Test is one step towards assuring those further down the supply chain of the ethical provenance of an individual stone.

Gubelin Gem Lab recognises that the cost of the Paternity Test system, like that of blockchain technology, may be prohibitive for smaller operators. It states that it wants to “avoid small and artisanal miners getting side-lined” by finding “ways to make the technology accessible and affordable for them.” The lab says it is working with governments and civil society to achieve this57“Proof of Provenance”. Gem-A blog post. 31st July 2019. https://gem-a.com/news-publications/news-blogs/gems-from-gem-a/gem/proof-of-provenance.

3. Bad practices, rightly abhorred

Gemstones are small, valuable and non-perishable - properties that make them attractive for a number of illicit activities. Nonetheless, high-profile reports of wrongdoing are by no means representative of the vast majority of coloured gemstone trading. Most dealers in coloured gemstones rightly abhor the worst excesses of the trade, which bring honest businesses into disrepute by association and ultimately impact traders’ ability to practice they profession successfully.

We examine bad practices in this section; taking stock of issues that are of common to concern to ordinary traders, retailers, customers, and all who wish to see a thriving, modern, ethical coloured gemstone sector.

Smuggling and tax avoidance

Cross-border smuggling in some quarters of the coloured gemstone sector is reportedly common58For example, see “The Truth About Gem Smuggling”. Ganoksin website. Accessed 21st October 2021. https://www.ganoksin.com/article/truth-gem-smuggling/. Gemstones may be smuggled out of their country of origin in order to avoid export taxes, or bans on the export of rough stones, but there are also other, more relatable reasons why traders smuggle. These include onerous paperwork requirements for export, costly delays at customs and requests for bribes from corrupt officials, like undervaluation of gemstones, discussed above, smuggling deprives producer countries of revenues from the gemstone trade.

Smuggled gemstones are sometimes represented as originating from the country they are smuggled to, especially if that country is a prestigious producer of coloured stones. For example, sapphires from Africa are often smuggled to Sri Lanka59For example, see “Sri Lankan student ordered to pay Sh10 million fine for smuggling gemstones”. The Citizen (Tanzania). 27th September 2019. https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/news/Sri-Lankan-student-ordered--to-pay-Sh10-million-fine-for/1840340-5290052-gtwxdf/index.html where they are sold as local “Ceylon” sapphires instead. African sapphires are often much cheaper, so re-designating them as Ceylon sapphires can turn a good profit.

Smuggling to Sri Lanka is reportedly particularly common for Madagascan gemstones. According to Michael Arnstein, the president of a US-based gemstone business interviewed by The Guardian newspaper, “about 70% of [Madagascar’s] sapphire market [is] controlled by Sri Lankans, who smuggle the gems back to their country to be cut and exported for sale. About $150m worth of sapphires might leave Madagascar every year, though the exact figure is impossible to know as the industry is not well regulated60“'Sapphire rush' threatens rainforests of Madagascar”. The Guardian. 2nd April 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/02/sapphire-rush-threatens-rainforests-of-madagascar.”

While such practices are clearly detrimental to the Madagascan national budget, their underlying cause may be more about systemic export difficulties than traders’ desire to avoid taxes. Speaking anonymously, an international gemstone trader explained for this paper:

“If you want to export legally from Madagascar then you have to set aside a few days in the capital to arrange all the paperwork, and there’s very little clarity on what you can take out, in terms of volumes or gem types. Tax is only 2%, but gems need to be sealed, stamped and have all the required export documents. Bribery and corruption are issues. Officials hope to get payoffs so they create delays. They make it take hours and days to get gemstones out legally. The cost of sending is huge, it could cost US$260-$325 to export. Once you’ve added in the taxes from the Malagasy side and the destination country taxes it can cost US$500 for a small parcel of sapphires.”61Interview conducted in July 2019.

In another example of unofficial exportation, gemstones are frequently smuggled from Myanmar to Thailand62“Burmese Gem Smuggling is Part of Border Life”. Ezine Articles. 8th August 2006. https://ezinearticles.com/?Burmese-Gem-Smuggling-is-Part-of-Border-Life&id=263289. With a 2,100km shared border and limited policing for gemstone trafficking, smuggling of gemstones is relatively straightforward between the two countries. From Thailand the stones are then traded onward into international markets.

The disparity in trade figures between Myanmar and Thailand gives an indication of the scale of the phenomenon. In 2016, Myanmar recorded just over $ 1.8 million in exports of uncut precious and semi-precious stones to Thailand, whereas Thailand recorded receiving US$4.7 million worth of stones. The difference in the two figures is likely primarily attributable to smuggling63“‘Genocide gems’: Highly-sought Burmese rubies and sapphires may be enriching Myanmar’s military”. Canada Global News. 4th November 2018. https://globalnews.ca/news/4571806/burmese-ruby-genocide-gem-myanmar/.

Organised crime

There are few concrete links documented between the traditional coloured gemstone trade and international organised crime. However, such activities are by their nature clandestine, and links may exist. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the gemstone trade in Pakistan is used to facilitate money laundering, drug smuggling and terrorist financing, for example (see the case study below, Two Countries, One Trade: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Conflict and Coloured Gemstones).

Parallels with the diamond industry indicate some potential for illicit links. A 2013 report by the Financial Action Task Force, Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Through Trade in Diamonds64“Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Through Trade in Diamonds”. Financial Action Task Force. October 2013. http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/ML-TF-through-trade-in-diamonds.pdf details connections between the diamond trade and “drug trafficking, fraud, smuggling, theft and robbery, large scale tax offences, forgery and fictitious invoices among other offences” and states that of these “drug trafficking and smuggling were found to be the most prevalent”, though it did not attempt to quantify the scale of these issues. The report cites the globalised nature of the diamond trade, lack of traceability, difficulties in valuation, high dollar values and low awareness from law enforcement bodies as key characteristics that make diamonds attractive to criminal groups. These characteristics also apply to some of the more valuable coloured gemstones, including rubies, emeralds and sapphires.

However, the huge variance between coloured gemstones, and the challenges of defferentiating valuable stones from others, could make coloured stones a less valuable 'currency' for organised crime, compared to relatively-uniform diamonds. While it should not be assumed that links between coloured gemstones and organised crime are sparse, it should not be assumed they are widespread either, in the absence of solid evidence.

Fuelling Conflict

When trade in gemstones is controlled by paramilitary, insurgent or militia groups, revenues can fuel armed conflict through the purchase of arms and of other resources needed for warfare. While in no way representative of the vast majority of the trade, there are instances of coloured gemstones being used in this way. Rubies mined in Cambodia and sold in Thailand in the 1980s and 1990s were used to fund the Khmer Rouge insurgency65“Rubies Are Swelling the War Coffers of Cambodia’s Feared Khmer Rouge Rebels”. Los Angeles Times. 18th November 1990. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-11-18-mn-6584-story.html. In Colombia, emerald mafias fought a long war over control of the gemstone trade with the country’s drug cartels (discussed in more detail in another paper in this series Hands that Dig, Hands that Feed: Lives Shaped by Coloured Gemstone Mining). Contemporary fears have been raised over possible links between tourmaline mining and non-state armed groups in the eastern areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo.66“Coloured Gemstones in Eastern DRC: Tourmaline Exploitation and Trade in the Kivus”. IPIS. 11th May 2016. https://ipisresearch.be/publication/coloured-gemstones-in-eastern-drc-tourmaline-exploitation-and-trade-in-the-kivus/

Perhaps the most prominent modern conflict associated with coloured gemstones, however, is in Afghanistan and Pakistan. The trade in lapis lazuli and other coloured gemstones in Afghanistan has been linked for decades to the funding of militant groups including, most recently, the Taliban.

Two countries, one trade: Afghanistan, Pakistan, conflict and coloured gemstones

The Afghan province of Badakhshan is rich in fine rubies, tourmaline, spinel, aquamarine and lapis lazuli, while high quality emeralds are mined in the neighbouring Panjshir Valley. Past wars, contemporary conflict, weak governance and inadequate infrastructure mean that Afghanistan’s mineral assets67These assets include important deposits of lapis lazuli, emeralds and rubies, as well as copper, iron, gold, silver, chromium, marble and coal. See "Summaries of Important Areas for Mineral Investment and Production Opportunities of Nonfuel Minerals in Afghanistan". USGS, 2011: https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2011/1204 have not seen large-scale development. The country does, however, have a thriving artisanal and small-scale mining sector, which focuses on resources suited to manual and low technology mining processes, such as gemstones and marble.

Afghan gemstones have funded militants since the time of the anti-Soviet mujahideen in the 1980s, through the Jamaat-i-Islami and United Islamic Front in the 1990s to the Taliban up until the group seized power nationwide. In 2005 the Afghan Ministry of Mines estimated that 80% of the country’s mines were under the control of non-state armed or criminal groups68“Afghanistan’s Conflict Minerals: The Crime-State-Insurgent Nexus,” CTC Sentinel, Vol. 5(2), p13. February 2012. https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2012/02/CTCSentinel-Vol5Iss27.pdf.

Corruption is endemic in Afghan commerce69“Afghanistan’s Anti-Corruption Efforts”. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. November 2019. https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/audits/SIGAR-20-06-AR.pdf. Much of the illegal gemstone mining, transportation and trading that takes place in Afghanistan was widely perceived to be linked to high level officials in the previous Western-backed government, profiting at the expense of the national treasury. A 2016 report by the NGO Global Witness, “War in the Treasury of the People: Afghanistan, Lapis Lazuli and the Battle for Mineral Wealth”70“War in the Treasury of the People: Afghanistan, Lapis Lazuli and the Battle for Mineral Wealth”, p7. Global Witness. 30th May 2016. https://www.globalwitness.org/afghanistan-lapis/ estimated that a full 95% of potential government revenues were lost from certain of Afghanistan’s lapis lazuli mines in 2015.

The same report estimated that armed groups made US$ 12 million from lapis lazuli in 2015, US$ 4 million of which went to the Taliban. A 2015 Security Council report cites unnamed Afghan officials estimating Taliban income from mined sources overall at tens of millions of US dollars each year71“Letter dated 18 August 2015 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council”, p15. UN Security Council. 26th August 2015.

https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_2015_648.pdf. For comparison, the Taliban’s total overall revenue from all sources for 2011 was estimated by the UN at US$ 400 million72“Taliban raked in $400 million from diverse sources: U.N”. Reuters. 11th September 2012. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-un-taliban/taliban-raked-in-400-million-from-diverse-sources-u-n-idUSBRE88A13Y20120911.

Despite its association with conflict and corruption, there was never an easy or clear-cut case for international disengagement from the Afghan gemstone sector. Although the Taliban insurgency received funds from gemstone mines, it was not the Taliban who were doing the mining. Mining is typically carried out by individuals from nearby communities, many of whom subsist in economically precarious conditions, and rely on mining to provide additional income for their families alongside farming. If the Afghan gemstone trade had been halted, then this important source of income would have been removed.

Further downstream, the ethical picture is also complex. Afghanistan’s history of insecurity, and its limited domestic infrastructure for processing rough gemstones, mean that most Afghan gemstones are transported to Pakistan for cutting, polishing and onward sale. Afghanistan’s gemstones travel to Peshawar, Pakistan through the Khyber Pass border crossing, and along the myriad small paths that crisscross the neighbouring mountain ranges - well-trodden smuggling routes for drugs, arms and other commodities73“The Dangerous World of Pakistan’s Gem Trade”. McClean’s. 24th May 2014. https://www.macleans.ca/news/world/pakistans-blood-stones/.

Peshawar’s Namak Mandi is one of the world’s oldest gemstone markets. It sells rough and cut gemstones mined in Pakistan, as well as those that come across the border from Afghanistan. Anti-government insurgency in Pakistan’s gemstone mining regions74For context on insurgency in Pakistan’s gemstone mining regions, see “Taliban jihad against West funded by emeralds from Pakistan”, The Telegraph, 4th April 2009. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/pakistan/5106526/Taliban-jihad-against-West-funded-by-emeralds-from-Pakistan.html and in Afghanistan, and insecurity in Peshawar itself, have led to the gradual demise of the city’s traditional, commercial gemstone market, as international buyers have stopped coming. According to one article, “they have been replaced by money launderers, drug smugglers and terrorist financiers75“The Dangerous World of Pakistan’s Gem Trade”. McClean’s. 24th May 2014. https://www.macleans.ca/news/world/pakistans-blood-stones/.” The Financial Action Task Force, an inter-governmental body, has identified Pakistan as a monitored jurisdiction for trade-based money laundering, indicating a heightened level of risk76“High-risk and other monitored jurisdictions”. Financial Action Task Force website. Accessed 21st October 2021. http://www.fatf-gafi.org/countries/#high-risk.

Like the miners of Afghanistan, the traders of Namak Mandi do not aid insurgent and criminal groups as an end motive. They do so because they are entwined in a system that makes illicit activities an inevitable part of pursuing their livelihoods. At the same time as gemstone revenues are flowing to criminals and insurgents, they are flowing to gemstone workers’ families and often providing relief from desperate poverty. Preserving this good, while eliminating the bad, would require comprehensive reforms in governance and anti-corruption, and physical security gains, in Afghanistan and Pakistan. It would also require a degree of cooperation between Western governments and the Taliban. Some commentators have raised the possibility of an embargo on Afghan gemstones by the United States, though many in the coloured gemstone sector hope that, for the sake of local communities, this does not come to pass77“So What Happens To Afghanistan’s Gems Now?” Rob Bates. JCK Magazine Online. 21st October 2021. https://www.jckonline.com/editorial-article/happens-afghanistans-gems/.

Sustaining systems that violate human rights

Just as coloured gemstones can sometimes be used by insurgent groups to build their power base, they can be used by regimes that are already in power, to stay there. In Myanmar, for example, the country’s military has historically held extensive commercial interests in gemstone mining, particularly for jade. Large quantities of rubies are also mined in Myanmar, though generally at smaller, less industrialised mines, and the military generally has less control over their onward trade and export that it does for jade.