Coloured Gemstones:

Ancient Crafts, Modern Challenges.

Introduction

Gemstones are wealth. For countless centuries they have been sought out, bought, sold, coveted, treasured, and used as pivotal expressions of cultural and individual identity. They reach their apogee of value as brilliantly cut and polished pieces, wrought together with precious metals and other fine materials, but each step along their earlier path imparts wealth into the hands they pass through.

Today, the coloured gemstones sector sustains the livelihoods of millions of workers and craftspeople around the world. The stones they produce and process are rising in value, as coloured gems enjoy the attentions of a new generation of retail customers, keen to look beyond diamonds for a richer range of jewels. New value can mean new wealth for gemstone miners, traders and artisans, and new revenue streams for local and national budgets. A real opportunity exists today for sustainable development in some of the world’s poorest communities, fuelled by coloured gemstones, but this opportunity can only be realised with coordinated and well-crafted action in support of responsible sourcing, and other reforms.

This series of papers takes a step in that direction, by equipping the reader with relevant knowledge, by presenting the varying perspectives of different groups within the sector, in a balanced manner, and by pointing toward routes for improvement in the sector where they exist. Consequently, this resource helps to enable the reader to play an active role in promoting positive change – whatever their own relationship to the sector may be.

Our White Papers are also available to download and read offline.

Please fill in your details to receive a download request.

TDi Sustainability has researched and written this series of papers, following the journey of coloured gemstones from the mines that produce them to the hands of retail customers, with the support of the Coloured Gemstones Working Group. The Group is a collection of leading luxury jewellery brands and gemstone miners, comprising the companies; Tiffany & Co., Swarovski, Richemont, The Muzo Companies, LVMH, Kering, Gemfields and Chopard.

These companies chose to support TDI Sustainability’s research, in order to create a resource for all those whose lives and livelihoods are touched in some way by coloured gemstones. As gemstones travel from shovel to showroom we paint a picture of the people and institutions that they encounter along the way, we map the environmental, social and governance landscape that they pass through, and we explore how the coloured gemstone sector can take confident strides into the arena of responsible sourcing.

We believe that the most profound improvements to the coloured gemstone sector can be brought about when all those within it are striving for better environmental, social and governance conditions, collectively. In this spirit of inclusivity, this series of papers have been written in an accessible style, with the least possible amount of industry jargon or formal phraseology.

Nonetheless, the research underpinning these papers has been rigorous. As we developed them, we placed importance on listening to, and incorporating, the voices of individuals and institutions representing different points of view, to ensure broad analysis and to present accurate and balanced perspectives. We have reviewed existing open source literature and have conducted interviews and peer review consultations with a wide range of industry experts, civil society representatives and supply chain participants, who have helped shed light on complex issues from their first-hand experience.

The diversity of voices we have listened to in writing these papers is reflective of the diversity of the coloured gemstone sector itself. There are over fifty different types of coloured gemstone, mined and traded, cut and polished in all corners of the world, and the journey of each stone from the earth to an end customer is unique. It would not be possible to describe every aspect of the rich world of coloured gemstones in a limited number of papers, so inevitably we have had to simplify and generalise complex issues, to an extent. These papers should be read as an introduction to the issues they describe, and a jumping-off point for research and debate, rather than as the final word on any matter.

While this series of papers is supported by the members of the Coloured Gemstone Working Group, TDi Sustainability maintained full editorial control, and the analysis is its own. In commissioning TDi Sustainability to write these papers on the challenges and opportunities present in the coloured gemstone sector, the Coloured Gemstone Working Group recognised the imperative to engage honestly and openly with stakeholders who are becoming increasingly well-attuned to corporate influence and the potential for companies to affect peoples’ lives. As our world becomes more interconnected, awareness is continuously rising among the general public, and within civil society and regulatory bodies, of the effects that choices at one end of a supply chain can have elsewhere - no matter how far removed in distance. Facing this rising awareness head-on, and harnessing it, can create a potent driving force for positive change. When companies pull together with their customers, their suppliers, and other stakeholders, supply chain conditions can be improved for the benefit of all.

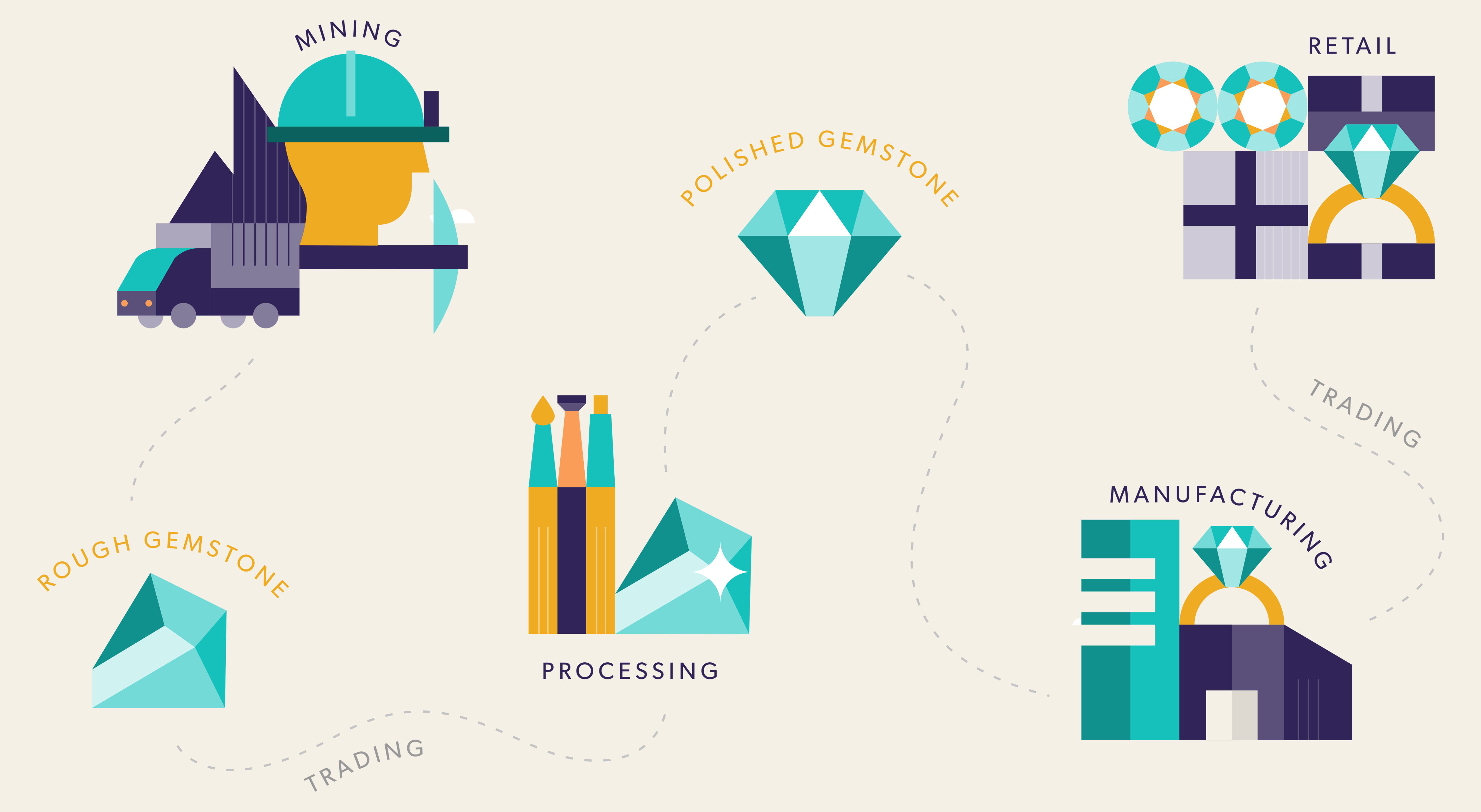

We examine the coloured gemstone sector by inviting the reader to follow the journey that gemstones undertake from mine to end customer. Along the way, we introduce the people, relationships and systems involved at each stage of the journey, and we examine for whom value is generated, for whom it is not, and how the status quo can be changed for the better. Following this introductory paper, the next papers describe key steps in the coloured gemstones supply chain; mining, trading, processing and retail. The final paper examines how the sector is governed, and how governance systems can adapt to rising expectations for responsible sourcing.

A shopper who is drawn to the allure of coloured gemstones might pick up a piece of tanzanite, tourmaline or topaz that catches their eye, and admire its clear, crisp brilliance under the bright light of its display cabinet - much as their parents or grandparents would have done in decades gone by.

This customer will likely be more mindful than his or her forebears, however, about the environmental and social impacts that can be associated with gemstone supply chains. The subject has received focused attention from the media and civil society in recent years, so today’s shopper is increasingly likely to wonder whether the ethical provenance of a gemstone is as unblemished and radiant as the stone itself.

In the absence of solid answers and assurances on ethical provenance, fears of the opposite may loom large for such a customer. Scenes from the film Blood Diamond, and the striking headlines of activist organisations’ reports, have done much to bring the worst excesses of the gemstone sector to life in the minds of the developed-world public, in recent years.

The 2013 briefing by World Vision “Behind the bling: Forced and child labour in the global jewellery industry,”1 for example, details multiple ways in which workers involved in mining gemstones and manufacturing jewellery are vulnerable to exploitation. Two reports by Global Witness, “Jade: Myanmar’s “Big State Secret”2 and “War in the Treasury of the People: Afghanistan, Lapis Lazuli and the Battle for Mineral Wealth,”3 reveal the association of gemstone assets with the funding of military ruling elites and of non-state armed groups such as the Taliban. The 2018 report by Human Rights Watch “The Hidden Cost of Jewellery”4 publicly scrutinises 13 major jewellery companies’ attempts to address human rights risks in their supply chains, against burgeoning international standards, and is sharply critical of most of their efforts. Activist reports such as these do not tell the whole story of coloured gemstones, since their purpose is to investigate the worst excesses of the sector and to hold companies and governments accountable for them. By doing so, such organisations create pressure for industry-wide reform – striving to reduce negative impacts while preserving and enhancing the many benefits that the coloured gemstone sector brings to communities worldwide.

Heightened awareness of the potential for environmental and social issues, deep in the supply chains of many everyday products, has given birth to a movement in responsible sourcing. Coloured gemstones are the most recent of materials that have come under the spotlight, but there are others. Businesses trading in the thick of global mineral supply chains are acutely aware of the regulatory obligations now attached to the sourcing of some metals. Tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold have become known for their association with conflict in some areas of the world. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a government-led body that has long set standards for corporate conduct, has developed guidelines to direct companies to undertake due diligence on their suppliers and supply chains and to publish the results, with a special focus on these four metals. These guidelines have recently been incorporated into EU law.

Regulations for disclosing procurement policies and due diligence outcomes have not yet permeated the coloured gemstone industry, but the responsible sourcing movement matters for the sector, nonetheless. Luxury and lifestyle brands, and boutiques, and the businesses that supply them, rise and fall on their ability to build and maintain a reputation of excellence and quality that increasingly extends to the provenance of raw materials, how they are mined and manufactured, and the way people and planet are affected along the way.

For many companies, responsible sourcing may represent an opportunity, as well as a challenge. Ethical products have carved a sizeable - and growing - niche in several sectors for two decades or more, serving an increasingly values-driven consumerism. In the jewellery business relatable stories of provenance are emerging as a distinct marketing aspect that some brands are incorporating into their identities and sales campaigns - not only for the aspirational brands parading pieces on the red carpet, but also at the affordable end of the market. Implementing an effective responsible sourcing programme without sacrificing commercial competitiveness, however, is not straightforward. This is true for any product, and the transparency challenges intrinsic to the coloured gemstone sector make this goal all the harder to reach.

A walk down the supermarket aisle reveals the profusion of environmental and social standards and labelling systems on offer to the consumer - from Fairtrade, Soil Association and Cradle-2-Cradle marks, to organic, shade-grown coffee and sustainable fishing initiatives. You will not have the same experience when shopping in Paris’s epicentre of high jewellery, Place Vendôme, or at your high street jewellery boutique, or indeed in most outlets for the majority of luxury goods.

The coloured gemstones retail sector has built its reputation on its credentials of design innovation, manufacturing excellence and material quality, but it is new to the world of voluntary standards that promise traceability and responsible production. One reason for this is the anatomy of the industry. Coloured gemstone supply chains are highly complex, making full supply transparency more challenging than for other commodities such as tea or coffee, cut flowers, bananas or industrially mined minerals.

Coloured gemstones are mined in nearly 50 countries spanning all continents, besides Antarctica. Their journey from the mine to consumer typically involves a wide network of interdependent individuals, families, businesses and institutions. A coloured gemstone can change hands up to 50 times throughout its journey. The great majority of coloured gemstones, at least 80 per cent, are mined by Artisanal and Small -Scale Miners (ASM)– individuals, families or small groups of workers using rudimentary tools and often operating in the informal, unregulated sector of the market.

Unlike consumable commodities such as fruits, gemstones may not take a linear path to the end customer. They can be traded back and forth many times, between networks of dealers looking for the right stones for their clients, or in exchange for other goods and services. And they can be stored (or worn) for decades before re-entering the market once again.

The challenges don’t even end there. Gemstones’ small size and the difficulties inherent in traceability and valuation mean that they are easily smuggled, and are well suited to money laundering, and for use by organised crime, further complicating the ethics of the gemstone trade.

Map providing an overview of top coloured gemstone producer countries, gemstone processing and jewellery manufacture hubs and key gemstone trade routes (note: many high-end jewellery brands manufacture luxury pieces in European countries including France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland, though these countries have been omitted from the map due to the low volumes of gemstones that pass through them, compared to Asian manufacturing hubs).

Worth an estimated $10bn a year, the non-diamond gemstone sector plays an important economic role for many developing countries. Because of the prevalence of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM), and through a cutting and polishing industry that involves hundreds of thousands of craftspeople and small businesses, and feeds supporting industries, the coloured gemstone sector provides livelihoods for many millions worldwide. In some corners of the globe, gemstones are a source of income for communities that have very few other options by which to sustain themselves. And, as well as being an economic lifeline, gemstones can represent an opportunity for a family or community to coalesce around a common endeavour, using skills passed from generation to generation, crafting world-class jewels without recourse to aid agencies or governments for assistance. Larger companies, meanwhile, are increasingly entering the coloured gemstone sector alongside their small-scale counterparts, providing tax revenues for public budgets and investment into local communities.

The gemstone sector also has its downsides, however. For example, uncontrolled gemstone mining can degrade natural habitats, child labour can sometimes be used at informal mine sites, gemstone trading can be associated with illicit financial flows, as touched on above, and cutting and polishing workers can face respiratory health hazards if precautionary measures are not taken.

With a sound understanding of these upsides and downsides at each stage of the supply chain, and of the opportunities and challenges for responsible sourcing that coloured gemstones present, everyone who is involved in the sector can help it to evolve, by playing a role in the endeavours and initiatives that exist, or could come into being, to shape it. This can ensure that the future of coloured gemstones retains as many as possible of its current virtues, and augments them, while mitigating its negative aspects.

Mining

Coloured gemstone mining occurs in a great many countries across the globe, though each specific gemstone might only be found in a handful of mines – or even in just one unique deposit. The nature of the sector is largely shaped by geology and the nature of gemstones themselves, and we trace these roots. Historically dominated by small scale ‘artisanal’ mining, conducted with basic tools and little infrastructure, gemstone mining is changing as bigger and more modern players enter the sector. That’s not a change that suits everyone and we explore this trend, and others to do with the benefits and drawbacks of different types of mining, in the paper of this series, Hands that Dig, Hands that Feed: Lives Shaped by Coloured Gemstone Mining.

Trading

Gemstones may change hands dozens of times before reaching an end customer – their supply chains are extremely complex. They’re also highly informal, typically, and transactions are largely based on trust between trading parties. As such, traceability for coloured gemstones is uniquely challenging. Gemstones are hard to value, and this can lead to tax evasion, and to poor returns for miners. Smuggling and other criminal activity can also factor into a gemstone’s journey. Yet, from the point of view of people in the trade, there are good and legitimate reasons for it to stay the way it is. We examine these issues, and recent innovations in industry structure and in technology that may help to mitigate them, in the paper of this series, Oceans Apart? Conventions, Practices and Perceptions in Coloured Gemstone Trading.

Processing

This is the process that transforms a gemstone from a rough stone to a polished gem. It is undertaken by skilled craftspeople, often employed in small workshops. Occasionally, industrial machines are used to aid the process. Cutting and polishing adds a lot to the value of a gemstone and it can be a significant economic boost in countries where it takes place. It mainly happens in a few key worldwide ‘hubs’, though many people would like to see it move to less developed producer countries to maximise the benefits they reap from their gemstone endowments. We explore this aspiration, and other aspects of the cutting and polishing industry, in the paper of this series, Wheels of Fortune: The Industrious World of Coloured Gemstone Cutting and Polishing.

Retailing

Once gems are cut and polished, they are typically fashioned into jewellery and traded further before being sold to the end customer. The retail stage is where the greatest awareness of responsible sourcing issues exists, but there is remarkably little information available, in terms of hard facts, to help us understand this awareness. There is no real consensus on whether companies can expect to see commercial benefits from sourcing responsibly, or not, or the extent to which customers’ professed concern for responsible sourcing translates to their purchasing habits. We explore these aspects of a gemstone’s journey in the paper of this series, A Storied Jewel: Responsible Sourcing and the Coloured Gemstone Retail Sector.

Governing

Overarching all the steps above are the governance mechanisms that guide a gemstone’s journey and determine the flow of benefits, and how negative impacts are mitigated, along the way. Governance can take the form of national or international law, and regulatory oversight, or more informal ‘rules of the game’ observed by industry players. Governance can also mean voluntary standards initiatives, designed to ensure a more equitable distribution of wealth from the gemstone sector and to harness its development potential. We give an overview of gemstone industry governance, focussing on its responsible sourcing aspects, and suggest ways in which governance could potentially evolve, in the paper of this series, Letting it Shine: Governance in Coloured Gemstone Supply Chains.