Governance

Letting It Shine: Governance For Equitable Coloured Gemstone Supply Chains

Executive Summary

Letting it shine: governance for equitable coloured gemstone supply chains is the final paper in the Ancient Crafts, Modern Challenges series. In the previous papers in the series, we have seen how coloured gemstones are mined, traded, manufactured into jewels and sold to retail customers in jewellery. We have explored the ways in which coloured gemstones affect people and places along their journey, both positively and negatively.

The Coloured Gemstones Working Group, a collection of leading luxury brands and large-scale mining companies, commissioned this series of papers to demystify the complex, traditional and skill-rich coloured gemstone sector, and to explore how the sector can develop in line with rising expectations for responsible sourcing.

We conclude our series by taking stock of some of the insights we have gained, about the underlying social and economic systems that make the coloured gemstone sector the way that it is, and we consider how these systems could evolve positively in future.

This paper examines current levels of governance in coloured gemstone supply chains, which often start with small-scale operators in low-income countries. It assesses the source of the current global impetus for greater governance of coloured gemstones, and maps some of the key entities in the governance landscape: governments in gemstone-producing and gemstone-destination countries; industry associations in gemstone-producing countries; and the international bodies that act as custodians of voluntary best-practice frameworks for the private sector. The paper looks at some practical examples of how governance is exercised over the coloured gemstone sector, with a focus on Sri Lanka and Thailand, and considers the governance challenges that are present when large-scale and small-scale coloured gemstone miners work in close proximity.

We assess the significant challenges of achieving full stone-by-stone traceability of coloured gemstones, which is a rising trend for many other material supply chains. We explore some of the systemic issues underpinning these challenges – in particular, the trade-off between ‘inclusivity’ and ‘assurance’. The stronger a scheme’s assurance of supply chain social and environmental performance, the greater the risk that small businesses, unfamiliar with such schemes and with few resources to respond to them, will be able to participate in them or meet their requirements.

We conclude this paper, and this series of papers, by proposing a possible credible system for supply chain traceability for coloured gemstones: a ‘chain of confidence’ that combines the principles of traceability embodied in best-practice frameworks, including the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, with a pragmatic appreciation of the reality of coloured gemstone supply chains.

Coloured gemstones embody wealth. Supply chain participants, from miners to retail customers, are united in a desire to see that wealth distributed fairly. Effective responsible sourcing schemes for coloured gemstones can support this aim and could bring genuine gains to the millions of people around the world who depend on coloured gemstones for their livelihoods.

Our White Papers are also available to download and read offline.

Please fill in your details to receive a download request.

Introduction

Coloured gemstones owe their physical structure to the forces of nature, but their value is determined by humankind. The distribution of that value, among the many hands through which a gemstone passes on its journey from the earth to an end customer, is shaped by governance.

Governance can mean different things to different people – many definitions and interpretations of the word are used, in many different contexts in public discourse. For this paper, we take ‘governance’ to mean the governance of natural resources, for which the International Union for Conservation of Nature offers a concise definition1Natural Resource Governance Framework. International Union for Conservation of Nature website. https://www.iucn.org/commissions/commission-environmental-economic-and-social-policy/our-work/knowledge-baskets/natural-resource-governance (accessed 24th November 2021):

Natural resource governance refers to the norms, institutions and processes that determine how power and responsibilities over natural resources are exercised, how decisions are taken, and how citizens – women, men, indigenous peoples, and local communities – participate in and benefit from the management of natural resources.

In concrete terms, natural resource governance shapes key aspects of resource use, such as how taxation is applied, to whom and at what rate, how workers’ rights and the environment are safeguarded, what responsibilities companies have to communities, and companies’ obligations for commercial probity and disclosure.

Mined materials, such as coloured gemstones, are a finite resource. Deposits can last for a few years, or a few decades, but once they are expended, they are gone forever. For developing countries, governance can determine whether these one-off opportunities are realised or squandered. With good governance, coloured gemstones can provide livelihoods for legions of workers and can drive national economic development, without severely impacting local communities or the natural environment. When governance is poor, the value of a country’s coloured gemstones may only be realised beyond its borders, or may be lost entirely, to waste, mismanagement and corruption, accompanied by environmental degradation and social strife.

Governance of natural resources can be instituted by many different types of organisations. National governments are the most obvious agents of governance, but governance can be multi-layered, with contributions from companies in the supply chain, voluntary sustainability standards, industry associations at the sub-national, national or international level, and from other entities too.

In this paper we will discuss governance challenges in the coloured gemstone sector, and the current worldwide impetus for reform. We will look at the various types of organisations active in gemstone governance, and look at routes through which governance could evolve, particularly through responsible sourcing, to support a more equitable and mutually beneficial sector, for its participants around the world.

The majority of coloured gemstone mining and rough gemstone trading takes place at small scales, in low- to middle-income countries. The World Bank estimates that at least 80% of sapphires are produced by artisanal and small-scale miners2Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining. The World Bank. 21st November 2013. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining (accessed 07th December 2021). Industry sources cite similar percentages for other types of coloured gemstones too3Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience, p8. Natural Resource Governance Institute. May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/governing-the-gemstone_sector-lessons-from-global-experience.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021) (though the figure is decreasing for rubies and emeralds due to the recent market entry of several large-scale mining companies). As discussed in another paper in this series, Glimmers in the Shadows: Perception and Reality in Global Coloured Gemstone Trading, the gemstones that small-scale miners produce are typically traded locally, and then internationally, through a web of individual operators and small businesses.

The International Colored Gemstone Association states that approximately 90% of artisanal and small-scale mining for coloured gemstones takes place in low- to middle-income countries4Colored Gemstones from Mine to Market: Ethical Trade and Mining Certification Challenges. International Colored Gemstone Association. 18th March 2010. http://www.diamonds.net/Conference/FairTrade/Docs/baselworld2010/Michelou_Basel2010.pptx (accessed 07th December 2021).

Small-scale enterprises in poorer countries can be associated with ‘informality’, which the World Bank describes as “labour and business that is hidden from monetary, regulatory, and institutional authorities”. Correlation is strong; according to the World Bank, 95% of informal employment takes place in emerging markets and developing economies5Yu, S., Ohnsorge, F. The challenges of informality. World Bank blogs. 18th January 2019. https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/challenges-informality (accessed 07th December 2021), and 90% of small- and medium-sized enterprises in the world operate informally6Zhenwei Qiang, C., Ghossein, T. Out of the shadows: Unlocking the economic potential of informal businesses. World Bank blogs. 7th December 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/out-shadows-unlocking-economic-potential-informal-businesses (accessed 07th December 2021).

It is no surprise, therefore, that many coloured gemstones mining and trading operations are informal, like many other small enterprises in the countries where they are based. Informal enterprises provide livelihood opportunities for countless millions of people, who have few good options to participate in the formal economy. However, in some instances, the lack of oversight can lead to heightened social and environmental risks.

In Madagascar, for example, some observers have alleged that informal ‘rush miners’ at new gemstone finds significantly harm biodiversity and forest cover, and that these impacts persist after the gemstones have dried up and the miners have departed7Tullis, P. How Illegal Mining is Threatening Imperiled Lemurs. National Geographic. 6th March 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2019/03/sapphire-mining-fuels-lemur-deaths-in-madagascar/ (accessed 07th December 2021), because there is no governance mechanism in place to remediate them. The long-term impacts of rush mining have not been rigorously substantiated, because full environmental studies of affected areas have not been undertaken, and some commentators claim quick recovery times for impacted sites8Pardieu, V. Is the sapphire trade really driving lemurs towards extinction as Paul Tullis claims on National Geographic? - A response by Vincent Pardieu. LinkedIn Blog. 21st March 2019. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/sapphire-trade-really-driving-lemurs-towards-paul-tullis-pardieu/ (accessed 07th December 2021). Regardless of the true scale of long-term impacts in Madagascar, however, the environmental risks associated with unconstrained mining in pristine wilderness are clear.

Informal small-scale mining can also be associated with the Worst Forms of Child Labour, which is defined by the International Labour Organisation9C182 - Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention. International Labour Organisation. 17th June 1999. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C182 (accessed 07th December 2021) to include work in hazardous environments such as underground mines. According to the civil society organisation Verité, coloured gemstones are mined using child labour in Madagascar, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia10Gemstones other than Diamonds: Summary of Key Trafficking in Persons Issues in Gemstone Production. Verité website, https://www.verite.org/africa/explore-by-commodity/gemstones-other-than-diamonds/ (accessed 07th December 2021).

Informality in gemstone mining and trading can lead to taxation shortfalls. In particular, when gemstones are smuggled across borders by informal traders, revenue collection by governments becomes extremely challenging. Looking again at Madagascar, some sources estimate that US$150 million worth of sapphires and other coloured gems are smuggled from the country to Sri Lanka every year, depriving the Madagascan government of much-needed income11Tullis, P. How Illegal Mining is Threatening Imperiled Lemurs. National Geographic. 6th March 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2019/03/sapphire-mining-fuels-lemur-deaths-in-madagascar/ (accessed 07th December 2021)12'Sapphire rush' threatens rainforests of Madagascar. The Guardian. 2nd April 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/02/sapphire-rush-threatens-rainforests-of-madagascar (accessed 07th December 2021). In southeast Asia, gemstone smuggling from Myanmar to Thailand is reportedly commonplace, perpetrated both by individual traders and organised armed groups13Mac, D. Burmese Gem Smuggling is Part of Border Life. Ezine Articles. 08th August 2016. https://ezinearticles.com/?Burmese-Gem-Smuggling-is-Part-of-Border-Life&id=263289 (accessed 07th December 2021). A presentation by the Communities and Small-scale Mining (CASM) initiative, which was supported by the World Bank and DFID, makes even more striking claims, though some are historical and it does not provide references through which these claims could be further substantiated14Conflict Gems: Mining, Marketing & Terror Funding In Relation To ASM. Communities and Small-scale Mining initiative. 12th November 2008. http://artisanalmining.org/Repository/01/The_CASM_Files/CASM_Meetings_International/2008_Brazil_AGM/Presentations_structured/Workshop_1_SD_and_Security/Usman_-_Conflict_gems.ppt (accessed 07th December 2021):

In 1996, the Colombian government officially valued its emerald exports at $180 million and said illegal exports — i.e., those for which no taxes or royalties were paid to the Colombian government — were more than 10 times that amount. According to a 2001 report funded by [the US Agency for International Development], 45% of Tanzania’s coloured gem production is smuggled out of the country, and legal exports were undervalued by 50%. Pakistan estimates illegal gem sales at “more than 100 times” legal gem sales, and it is impossible to make any serious estimate of smuggling out of Myanmar or Afghanistan.

Small-scale enterprise is not incompatible with sound governance, just as large-scale enterprise is no guarantee of good governance15For context on governance issues associated with large-scale mining, comparative to small scale mining, see Why Cutting Off Artisanal Miners Is Not Responsible Sourcing. Global Witness. 26th November 2019. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/blog/why-cutting-artisanal-miners-not-responsible-sourcing/ (accessed 07th December 2021). We saw in another paper in this series, Hands That Dig, Hands That Feed: Lives Shaped by Coloured Gemstone Mining, that Australia has a system of governance by which casual gemstone “fossickers” can co-exist successfully with large mining companies, and in the Spotlight on Sri Lanka section, below, we discuss the provisions that are in place in Sri Lanka to ensure that small-scale mining is well governed. Effective governance systems can be instituted even in low-income countries, if they are pragmatically tailored to realities ‘on the ground’. Demand is growing for greater governance in the coloured gemstone sector, and many different institutions and organisations have roles to play in implementing it.

Civil society, companies in the supply chain and governments themselves all give impetus toward greater governance in the coloured gemstone sector.

As discussed in another paper in this series, A Storied Jewel: Responsible Sourcing And Retailing Of Coloured Gemstones, NGOs play an important role in shaping public perceptions of environmental and social issues associated with raw material production, including in the coloured gemstone sector. NGO reports often identify potential governance gains as a route to mitigate negative impacts, and make recommendations to national governments, private sector companies and international organisations accordingly16See, for example, War in the Treasury of the People: Afghanistan, Lapis Lazuli and the Battle for Mineral Wealth, p8-9. Global Witness. June 2016. https://www.globalwitness.org/documents/18528/war_in_the_treasury_printv6a_lr_G2pfYBL.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

This civil society pressure is one contributing factor to the current impetus for governance in the coloured gemstone sector. Another factor is responsible companies’ own proactive efforts to respect human rights and reduce environmental impacts in their supply chains, in line with best-practice frameworks such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights16Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. UN Office of the High Commissioner. 2011. https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). Companies in the coloured gemstone supply chain increasingly promote good governance with their suppliers, using tools including those developed by the Gemstones and Jewellery Community Platform17The Gemstones and Community Platform [website] https://www.gemstones-and-jewellery.com/ (accessed 07th December 2021) (which also hosts this series of papers), CIBJO18CIBJO Responsible Sourcing Toolkit. The World Jewellery Confederation (CIBJO). https://www.cibjo.org/rs-toolkit/ (accessed 07th December 2021) and the Responsible Jewellery Council19Code of Practices 2019. Responsible Jewellery Council. https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/standards/code-of-practices-2019/ (accessed 07th December 2021).

Naturally, impetus for governance also comes from national governments themselves, responding to the demands of their citizenry. Governments are responsible for managing their countries’ wealth and promoting their citizens’ wellbeing. As such, they are expected to set policies that mitigate negative social and environmental impacts associated with coloured gemstone production, to ensure that taxation and trade policies are set effectively, and to ensure that the rights to access deposits and exploit resources are granted fairly, under terms that are beneficial for all parties. They are also expected to create an enabling environment in which ‘value-add’ industries such as cutting and polishing can operate successfully. They must also police the sector, ensuring that its participants play by the rules. In some cases, governments might engage in the coloured gemstone sector directly too, through state-owned enterprises, which they must ensure are efficient and well run.

Growing market demand for coloured gemstones, and corresponding price rises,20 Hailes, S. Revealed: Why are coloured gemstones on the rise and what are consumers looking for?. Professional Jeweller. 17th June 2019. https://www.professionaljeweller.com/revealed-why-are-coloured-gemstones-on-the-rise-and-what-are-consumers-looking-for/ (accessed 07th December 2021) give governments in gemstone-producing countries additional impetus to govern the sector effectively. With more value available from the sector, it becomes more worthwhile for governments to pay attention to how that value is captured and distributed.

National governments in gemstone-producing countries

National governments in gemstone-producing countries play a central role in determining who participates in the coloured gemstone sector, who benefits and how, and in what ways negative impacts are managed. Among other things, national governments are responsible for setting and implementing taxation policies and establishing an enabling environment for the private sector – both large and small scale.

Faced with highly informal coloured gemstone sectors, operating beyond the control and oversight of the authorities, some governments have attempted to introduce formal large-scale mining, and to promote it above small-scale operations. In jurisdictions such as Colombia, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia, for example, governments have granted concessions to large-scale miners, recognising the potential for taxation revenues and other economic benefits that they represent. In some cases, these large-scale operations have displaced small-scale miners.

Revenue flows from large-scale mining can certainly be significant. For example, the company Gemfields:

- Pays the equivalent of 23 cents of every dollar earned in Mozambique to the government, when all taxes and royalties are taxes in aggregate.21Data provided by Jack Cunningham, Group Sustainability, Policy and Risk Director, Gemfields Ltd. October 2019.

- Conducts ruby auctions in Mozambique that raised US$ 512.6 million in the period June 2014 to June 2019.22Gemfields Group Limited. Singapore Ruby Auction Results. 18th June 2019. https://gemfields.s3.amazonaws.com/News%20and%20Announcements/2019/June/20190618%20GGL%20SENS%20announcement%20-%20Singapore%20ruby%20auction%20(final).pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

- Pays 18 cents of every dollar to the government in Zambia.

The large-scale emerald mines of Muzo in Colombia and Belmont in Brazil also generate significant tax revenues for their respective countries.

Relatively few coloured gemstone deposits worldwide are commercially viable for large-scale mining, and taxation of the small-scale coloured gemstone sector can be challenging. Gemstones concentrate a lot of value into items the size of pebbles. They are relatively easy to smuggle, compared to other commodities, and difficulties in valuation can lead to the manipulation of export prices23Ruth, L. The Truth About Gem Smuggling. Ganoksin. 2004. https://www.ganoksin.com/article/truth-gem-smuggling/ (accessed 07th December 2021). (for more detail on smuggling and valuation challenges, see another paper in this series , A Storied Jewel: Responsible Sourcing And Retailing Of Coloured Gemstones).

For those countries that do choose to levy taxes on small-scale traders, rates are typically low, lying in the region of 1-3% of a stone’s value24Shortell, P., Irwin, E., Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience. Natural Resource Governance Institute. May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/governing-the-gemstone_sector-lessons-from-global-experience.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

A comparison with the diamond industry demonstrates why this is: in Sierra Leone, a 6.5% royalty rate imposed on diamonds at point of export in 2009 (and a 15% supertax for diamonds worth more than US$ 500,000) caused a sharp drop in official exports, as stones were smuggled to Guinea or Liberia then shipped overseas. Two years later, the government was forced to reconsider the rate, reducing it to a more modest 3%.

Some governments choose to forego taxation on the gemstone trade altogether, and this can help to foster a more vibrant and successful industry overall – as shown in the Spotlight On Sri Lanka and Spotlight On Thailand sections, below.

Governments’ taxation policies rely on an effective civil service to be successful. In countries that suffer from weak rule of law and corruption, national governments face significant challenges in implementing and enforcing taxation policies and ensuring fairness in natural resource industries. Relevant issues can include poor separation between officials’ public powers and their private interests, unfair commercial competition fuelled by bribery and favour-trading, and the misappropriation of the benefits that arise from natural resource projects.25See, for example: Williams, D., Dupuy, K. At the extremes: Corruption in natural resource management revisited. U4 Brief. 2016. https://www.cmi.no/publications/5950-at-the-extremes-corruption-in-natural-resource (accessed 07th December 2021).

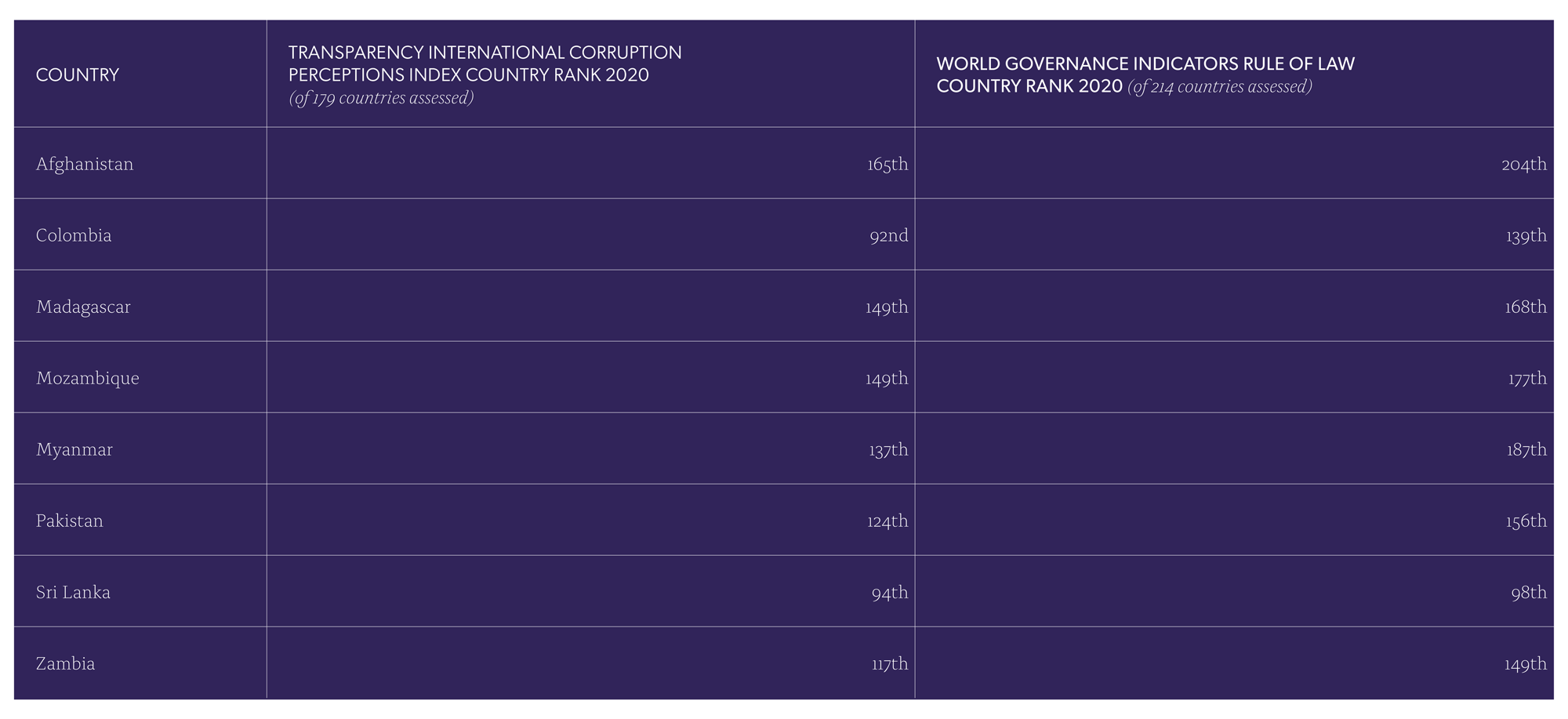

Efforts to mitigate these issues are important in the coloured gemstone sector since many gemstone-producing countries score poorly on relevant global governance indices.

Policy options for governments to manage their nation’s coloured gemstone sectors are relatively well covered in existing literature, such as the Natural Resource Governance Institute’s paper Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience.26Shortell, P., Irwin, E., Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience. Natural Resource Governance Institute. May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/governing-the-gemstone_sector-lessons-from-global-experience.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021) Less has been written on roles for other organisations in coloured gemstone governance. Below, we examine some of the roles that private sector organisations, associated bodies and initiatives, and governments in gemstone-destination countries can play, to help to ensure that coloured gemstone production, trading and processing is governed soundly, that negative impacts are well managed and that benefits flow fairly to stakeholders in the sector.

National and sub-national industry associations

National and sub-national industry associations can play an important governance role in countries where coloured gemstones are mined and traded. Such associations are common, though their strength and effectiveness vary significantly between countries.

Industry associations can act as intermediaries between small-scale miners and traders on the one hand and governments on the other. In countries where citizens are mistrustful of their governments, or do not feel that governments will uphold their rights or defend their interests, industry associations can offer a form of representation that is perceived by them as more legitimate.27Based on insight from an artisanal mining expert, interviewed for this series of reports.

As well as representing miners’ and traders’ interests, industry associations can also help to exert governance for small operators. For example, by only granting membership to those entities which have a legal licence to operate, and by sanctioning members that don’t conduct their operations in accordance with associations’ standards for responsibility.

By bridging the gap between governments and small operators, associations can help to ensure that expectations on both sides are pragmatic and achievable.

Tanzania’s experience with industry associations in the mining sector may be insightful for other countries. Tanzania has Regional Mining Associations (’REMAs’), that maintain relations with an overall Federation of Miners Associations, which has an important seat at the table for deciding how the mining sector in Tanzania is run. Although the REMAs do suffer from capacity constraints and leadership issues (some people allege conflicts of interest between REMA heads’ appointed duties and their private business interests), they nonetheless provide a channel through which ordinary miners’ views can be heard, and incorporated into the legislative process.28Mutagwaba, W., Tindyebwa, J.B., Makanta, v., Kaballega, D., Maeda, G. Artisanal and small-scale mining in Tanzania – Evidence to inform an ‘action dialogue’. International Institute for Environment and Development. 2018. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/16641IIED.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

The Federation of Miners Association of Tanzania (FEMATA) meeting in 2018. Source: FEMATA29[1] Federation of Miners Association of Tanzania-FEMATA. 8th November 2018. https://www.facebook.com/Federation-of-Miners-Association-of-Tanzania-FEMATA- (accessed 07th December 2021).1066408773545661/photos/1066427460210459 (accessed 07th December 2021).

Female artisanal miners in Tanzania have their own association, the Tanzania Women Miners Association, which lobbies for policy reforms and the allocation of resources to help develop legitimate women-led mining operations.30Mutagwaba, W., Tindyebwa, J.B., Makanta, v., Kaballega, D., Maeda, G. Artisanal and small-scale mining in Tanzania – Evidence to inform an ‘action dialogue’. International Institute for Environment and Development. 2018. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/16641IIED.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

The Tanzania Mineral Dealers Association, meanwhile, represents traders – particularly for the gemstone tanzanite. It cooperates with the government to foster rules and regulations that are well designed and helps to ensure that tax rates and systems are reasonable, and that taxes are collected effectively.31Mutagwaba, W., Tindyebwa, J.B., Makanta, v., Kaballega, D., Maeda, G. Artisanal and small-scale mining in Tanzania – Evidence to inform an ‘action dialogue’. International Institute for Environment and Development. 2018. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/16641IIED.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). (accessed 07th December 2021).

National governments in gemstone-destination countries

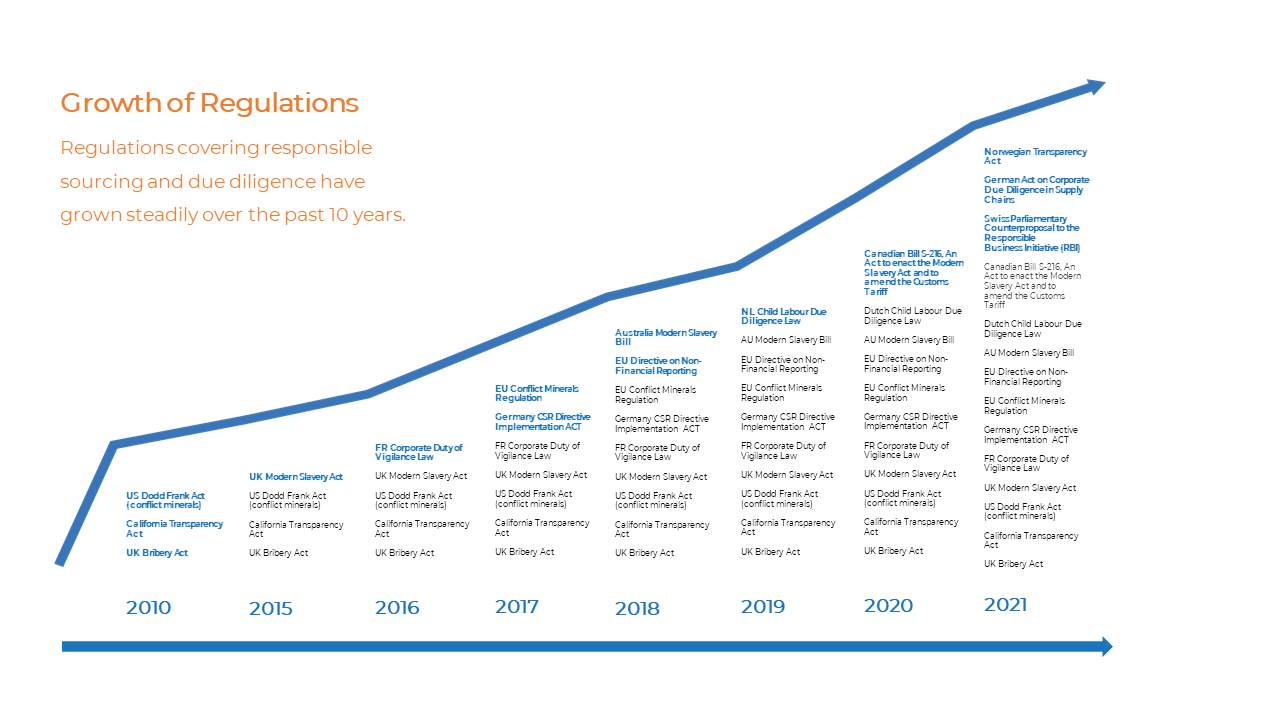

Governments in affluent gemstone-destination countries can provide funding and skilled professionals for governance programmes further up the supply chain, and this is a very typical assistance method. But these governments are also increasingly coming to realise that their own legislative environments can have a significant effect on the people further up the chain. The last 10 years has seen a rising tide of responsible sourcing and due diligence regulations in Europe and the US, which aim to mitigate negative impacts for people and planet, in countries further up supply chains.

Recent laws such as the German Supply Chain Act, the French Duty of Vigilance Law and the forthcoming EU Due Diligence Act establish a legal obligation for companies in these jurisdictions to investigate environmental and social risks in their supply chains. They are comprehensive regulations, governing all material types and all environmental and social risks.

Public attention on ‘conflict minerals’ has led to the creation of due diligence frameworks specifically focused on human rights risks and conflict financing in mineral supply chains, built on the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (the OECD DDG). These include Section 1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Act (2010), the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation (2017) and non-regulatory frameworks including the London Bullion Market Association and London Metals Exchange responsible sourcing requirements.

There are no specific legal requirements for due diligence in coloured gemstone supply chains at the moment. According to some reports, the US State Department may try to impose legal due diligence requirements on US companies in the sector in future,32 Bates, R. State Department Warns of Coming Jewelry Industry Crackdown. JCK. 16th April 2019. https://www.jckonline.com/editorial-article/state-department-warns-industry/ (accessed 07th December 2021). to combat money laundering and conflict funding, but no formal announcement has yet been made.

Nonetheless, the recent overall flow of supply chain legislation in Europe and the United States indicates a significant shift in public expectations for corporate behaviour. Companies in the coloured gemstone supply chain are increasingly adopting responsible sourcing programmes, in order to keep pace with these rising expectations. Some of the frameworks available to private sector companies for this purpose are discussed in the next section.

In addition to the regulatory route, governments in gemstone-destination countries also have a legislative route to promote good governance further up supply chains. In recent years, large mining companies operating in developing countries have been successfully sued in the developed countries where their headquarters are located, by community groups represented by top-flight law firms who usually work on such cases under a conditional fee arrangement. The results of such legal actions can sometimes be as much about governance reforms as they are about monetary compensation for losses.

In January 2019, for example, the coloured gemstone mining company Gemfields agreed to settle a case brought by the British law firm Leigh Day, regarding violent incidents at its Montepuez Ruby Mining site in Mozambique. In addition to a £5.8 million out-of-court financial settlement, which included Leigh Day's costs incurred in relation to the case, Gemfields agreed to establish an Operational Grievance Mechanism at the site for affected community members, in line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.33 Gemfields. Gemfields Press Statement. 29th January 2019. https://www.mining.com/app/uploads/2019/01/gemfields-press-announcement-jan29-2019.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). In this way, a company was compelled to institute site-level governance in much the same way that it otherwise could be by local legal requirements, or by the voluntary standards that it adhered to.

Voluntary best-practice frameworks for the private sector

Voluntary best-practice frameworks can be adopted by private sector companies to demonstrate their commitment to responsible business conduct. Such frameworks can focus on specific issue areas, or they can cover a wide range of environmental, social and governance issues. They can apply to a single commodity, or to the natural resource industries in general, and beyond.

Two of the most prominent responsible sourcing frameworks for the coloured gemstone sector are the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) Certification Scheme and the Coloured Gemstones Working Group’s (CGWG) Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform.

The RJC Certification Scheme allows participating medium- and large-scale companies to be assessed against the organisation’s Code of Practices. These cover a range of human rights, labour rights and environmental issue areas, with a strong focus on responsible mining and with provisions for responsible sourcing too. The Certification Scheme has historically focused on diamonds and precious metals, though it expanded in 2019 to cover rubies, emeralds and sapphires.

The Coloured Gemstone Working Group launched the Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform in April 2021, comprising educational and training tools, a library of templates that can be used in small businesses, a suite of self-assessments and a community exchange allowing suppliers and customers to collaborate and swap information about their performance and other aspects of their business. Resources on the platform include a learning module on responsible sourcing and a due diligence tool, designed to enable all supply chain entities, large- or small-scale, to build strong management systems for due diligence. The platform also allows companies to monitor the sustainability performance of their suppliers.

The RJC Code of Practices and the CGWG Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform both draw on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (the OECD DDG).34OECD (2016), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Third Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/mne/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-Minerals-Edition3.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). The OECD DDG mandates companies to investigate and address any association with conflict, serious human rights risks or illicit financial flows found in their supply chains through a structured stepwise process. It is widely used across the range of minerals industries, though the ‘chain of custody’ approach employed by many companies to implement the OECD DDG is challenging to apply to the predominantly small-scale, fragmented coloured gemstone sector. The challenges, and a potential solution, are discussed in the section Chains of Custody, Chains of Confidence.

Another challenge to small, independent coloured gemstone producer, manufacturer and trader participation in voluntary best-practice schemes is the cost associated with meeting site-level performance standards. The expense of upgrading practices and hiring third-party consultants for assessments can be prohibitive.

Efforts are underway to address these challenges, both in the coloured gemstone sector and in other sectors from which ideas can be drawn for the future.

One innovative approach is to combine standards, capacity development and investment into mining communities. The Impact Facility is one example of such an approach. The organisation is active in the gold, cobalt and coloured gemstone mining sectors, and according to its website it “seeks to bring economic and environmental empowerment to artisanal and small-scale mining communities”.35Impact Facility [website]. https://impactfacility.com/ (accessed 07th December 2021).

The Impact Facility is a sister organisation to TDi Sustainability, the organisation that has produced this series of six papers on the coloured gemstone sector.

In the coloured gemstone sector, The Impact Facility works in four areas:

- Improving productivity through better equipment

- Finding buyers that offer fair market terms

- Alternative livelihoods

- Helping mines meet buyers’ required standards

By offering miners economic support through activity areas 1 to 3, The Impact Facility incentivises miners to engage in the scheme, and to undergo training and capacity development to demonstrate that they can meet the basic operating standards expected in gemstone-buying markets in Europe, North America and Asia.

The Maendeleo Diamond Standards, backed by the Diamond Development Initiative, take a similar approach for diamonds. It is a certification scheme designed for the socio-economic context of artisanal and small-scale mining, to produce diamonds free of association with conflict, violence or human rights violations, while promoting environmental responsibility.36Resolve. Maendeleo Diamond Standards. Diamond Development Initiative. https://www.resolve.ngo/maendeleo_diamond_standards.htm (accessed 07th December 2021). The Maendeleo Diamond Standards employ a series of attainable basic benchmarks, combined with an innovative framework for continuous improvement over time. For example, in jurisdictions where artisanal and small-scale diamond miners cannot work legally because relevant legal structures do not exist, miners can still participate in the Maendeleo scheme, but should work with the authorities to establish appropriate legal frameworks for the future.37Ibid. The potential exists to transfer the benchmarks set by the Standards for artisanal and small-scale miners to coloured gemstone mining sites, to increase their environmental and social performance.

Further details on all the frameworks discussed here are given in Annex A: Five Important Voluntary Best-Practice Frameworks.

Non-monetary barriers to scheme participation

Schemes that aim to improve conditions for artisanal and small-scale coloured gemstone miners, and associated traders and gemstone manufacturers, must take a systemic approach to intervention if they are to succeed. The social and economic systems of small-scale coloured gemstone production are highly complex and require understanding and sensitivity.

In addition to monetary costs, small operators may face other, less obvious barriers to scheme participation, and to the formalisation of their work. For example, field gemmologist Vincent Pardieu shared his opinion for this report that:

Jealousy is a huge problem for small-scale miners. Anyone who is perceived as successful automatically attracts attention. Besides the costs, that’s a big reason why many small miners are afraid to formalise, to follow social and environmental standards, or do things in a transparent or accountable way. And that’s a huge challenge for governance initiatives that try to clean up the sector. If you are a small miner, it is safer if your mine looks like a disused junkyard, because if you try to do things in a clean and formal way then people around you start to think you are a millionaire. Your family, your friends will ask for money, and you might become a target for some nasty people. The worst thing you can do to yourself as a small miner is probably to adopt the sort of governance practices that a lot of international organisations advocate for.38 Interview with Vincent Pardieu conducted in July 2019.

Sri Lanka has produced coloured gemstones for centuries. It is most famous for its sapphires, and it also produces rubies, cat’s-eye chrysoberyl, spinel, garnet, beryl, tourmaline, topaz, quartz and many more gemstones besides. The island’s geological journey was uniquely well suited to the formation of coloured stones, so modern Sri Lanka is rich with alluvial gravels containing precious gems.

A handful of gem-bearing alluvial gravel, called illam in Sri Lanka. Image: Andrew Lucas/GIA

The alluvial nature of the deposits makes them easily accessible to artisanal and small-scale miners. The vast majority are mined by small groups using open-pit methods and basic tools, often as a form of seasonal income that supplements agricultural work. Mechanised mining and river mining also take place, but only in a few locations. Out of 6,500 mining licences issued in 2013, over 6,000 were for pit-mining operations.39Lucas, A., Sammoon, A., Jayarajah, A. P., Hsu, T., Padua, P. Sri Lanka: From Mine to Market, Part 1. GIA. 30th September 2014. https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research-sri-lanka-mining-part1 (accessed 07th December 2021).

This preponderance of licence awards to small-scale mines is not through lack of interest from mechanised operations. Mechanised licences are highly restricted. They are typically only issued when traditional methods are unsuitable for the deposit, the concentration of stones makes traditional methods economically unviable or if the deposit needs to be mined quickly due to the threat of illegal mining.40Ibid.

Many trade and regulatory bodies in Sri Lanka disfavour large-scale mining. In addition to the livelihoods benefits that artisanal and small-scale mining can bring, and the knock-on benefits for local traders and gemstone manufacturers, whom the government is keen to protect economically, some consider artisanal and small-scale mining a more environmentally-friendly method of extraction. The Sri Lankan authorities implement relatively strict environmental controls for small miners, including holding a deposit for each pit mine to ensure that it is filled in again once it has been exhausted. According to an article by GIA, this measure has ensured that a relatively small number of old Sri Lankan mining pits are left unfulfilled and the end of their lives, compared to the situation in many African countries.41Ibid.

Miners working by hand in an open pit in Sri Lanka. Image: Andrew Lucas/GIA

Sri Lanka also sets clear parameters for how gemstone mining revenues should be shared. 35% of gemstone income goes to miners, 35% goes to financiers, 20% goes to landowners and 10% goes to licence holders.42 Shortell, P., Irwin, E. Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience. Natural Resource Governance Institute. May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/governing-the-gemstone_sector-lessons-from-global-experience.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

Sri Lanka’s focus on small-scale local mining enjoys political support at the highest level, as the Sri Lanka Gem and Jewellery Association attests. It states prominently on the welcome page of its website: “President’s strict directive to the government officials: Keep foreign companies out of the local gem mining industry”.43Sri Lanka Gem and Jewellery Association [website] https://www.slgja.org/ (accessed 07th December 2021).

Political support for the local gemstone industry is reflected in government policy toward the sector. Gem and jewellery products do not incur import and export taxes, and cutters, polishers and jewellers do not have to pay income tax. The government has supported local cutters and polishers with training over many years, so the country now boasts 20,000 skilled craftspeople in the sector.44Shortell, P., Irwin, E. Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience. Natural Resource Governance Institute. May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/governing-the-gemstone_sector-lessons-from-global-experience.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). Through these measures, the government prioritises the health and growth of the industry over its potential to support the national budget – choosing economic vitality first and foremost. It also promotes Sri Lankan gemstones in overseas markets, through the National Gems and Jewellery Authority and the Export Development Board. Partially as a result of this wide-ranging government support, Sri Lanka today is one of the world’s foremost hubs for gemstone processing. The country cuts and polishes stones from East Africa and many other sourcing locations worldwide, alongside its domestically-mined stock.45Ibid.

Governance in the Sri Lankan gemstone sector is praised by many observers, and the information presented above suggests that it works well because each entity affected by the coloured gemstone sector is adequately incentivised to abide by the governance mechanisms that are in place. The miners, financiers, landowners and licence holders at mining pits all receive an agreeable share of income for their participation, and traders, cutters and polishers are not overly burdened by taxes and red tape that would otherwise entice them into smuggling.

However, the benefits of Sri Lanka’s gemstone policies are not felt universally. The country’s ‘light touch’ bureaucracy and taxation systems incentivise East Africa traders to ship rough stones to Sri Lanka for processing, rather than to attempt to have them cut and polished locally. In Madagascar, for example, virtually all sapphires are shipped – usually smuggled – to Sri Lanka and to Thailand. Thailand has a similar policy environment to Sri Lanka and is discussed in the next section. Because stones typically leave Madagascar rough and uncut, most of the value of Malagasy stones flows to craftspeople overseas.46James, C. Miners miss out on lucrative gains from Madagascar’s sapphires. France 24. 1st October 2019. https://www.france24.com/en/20191001-madagascar-sapphire-miners-poor-working-conditions-carved-abroad-value (accessed 07th December 2021). See also Madagascar – Illegal Sapphire Mining. Toby Smith [website]. https://www.tobysmith.com/project/madagascar-illegal-sapphire-mining/ (accessed 07th December 2021).

A Sri Lankan gemstone cutter using traditional hand-powered equipment. Image: Andrew Lucas/GIA

Thailand is the world’s foremost centre for gemstone cutting, polishing and treating – processes described in another paper in this series, Wheels of Fortune: The Industrious World of Coloured Gemstone Manufacturing. It is particularly renowned for its trade in sapphires and rubies. According to some commentators, most gemstones in circulation in the world today pass through the Thai city of Chanthaburi at some point in their journey,47[1] Unninayar, C. Chanthaburu – City of Gems. Gem Scene. https://www.gemscene.com/chanthaburi---city-of-gems.html (accessed 07th December 2021). either for processing or simply to be bought and sold by professional traders. Bangkok, meanwhile, has extensive markets for retail customers, supplying finished stones of all types, grades and sizes.

Thailand, August 12, 2017 - people trade at gemstone market in Chanthaburi, Thailand. Image: pemastockpic / Shutterstock.com

Thailand owes its prominence to the expertise of its craftspeople, in turning rough stones into sparkling jewels and items of jewellery and, above all, in the treatment processes they apply to dull or flawed stones to enhance their colour and appearance – and hence their value.

Stones that would have little worth in their untreated state are sourced from all over the world for the heat-treatment ’burners’ of Chanthaburi, and the benefits of this trade for the Thai economy are substantial. The gemstone and jewellery sector was ranked the third largest source of export sales in Thailand in 2015, worth US$ 6.6 billion. Approximately 1.3 million people are employed in the sector, mostly through small and medium enterprises.48Unninayar, C. The Ruby Capital of the World. Gem Scene. February 2016. https://www.gemscene.com/bangkok-feb-2016.html (accessed 07th December 2021).

Like the Sri Lankan government, the Thai government has created a supportive environment for its gemstone sector. In 2016, the government instituted a range of tax exemptions for individual traders. It waived VAT on imports of rough stones and introduced income tax exemptions on the onward sale of imported rough stones. Tax breaks were also given on the import of machinery and materials necessary for gemstone processing.49Ibid Also like Sri Lanka, however, Thailand’s pre-eminence for gemstone processing causes value to be concentrated in the country at the expense of its neighbours. In Thailand’s case, Myanmar is particularly impacted by the illicit export of rough stones,50Boot, W. Burma’s Frontier Appeal Lures Shadowy Oil Firm. The Irrawaddy. 09 May 2015. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/burmas-frontier-appeal-lures-shadowy-oil-firms.html (accessed 07th December 2021). which decreases opportunities for Myanmar craftspeople to enhance stones in-country.

The Thai Gem and Jewelry Traders Association51TGJTA [website] http://www.en.thaigemjewelry.or.th/ (accessed 07th December 2021). and the Chanthaburi Gem & Jewelry Traders Association52Chanthaburi Gem and Jewelry Traders Association [website] http://www.cga.or.th/ (accessed 07th December 2021). both represent members’ interests to the government, and thus play roles in ensuring effective governance of the gemstone sector within Thailand. Governance springs from less formal sources, too. For example, according to one report, the building owners at the Talad Ploy gem market in Chanthaburi typically charge a 5-15% commission on sales. In return, the owners try to ensure that synthetic or treated stones are not passed off as real or untreated stones within their buildings.53 Bhattacharya, S., Chowdhury, A., Abid, A. A market like you've never sheen. The Hindu. 29th July 2017. https://www.thehindu.com/thread/arts-culture-society/a-market-like-youve-never-sheen/article19384978.ece (accessed 07th December 2021).

Chanthaburi, Thailand Oct 15, 2017 - Colourful gemstones for sale at gemstones market in Chanthaburi town, Thailand. Image: Vassamon Anansukkasem / Shutterstock.com

The high proportion of the world’s coloured gemstones that pass through Chanthaburi make it an important focal point for potential future responsible sourcing efforts. The main international reference work for responsible sourcing, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas54OECD (2016), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Third Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/mne/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-Minerals-Edition3.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). (the OECD DDG, described in the section Voluntary best-practice frameworks for the private sector), stresses the importance of finding points in the supply chain where materials from diverse sources are concentrated and where information about steps higher up in the supply chain is available. The theory is that governance gains at identified points can be projected up the supply chain because of the large number of entities that are dependent on companies at identified points; they are thereby incentivised to adopt the governance controls they request.

Supply chain governance schemes typically call for traceability so that materials can be tracked up the chain. In gemstone hubs such as Chanthaburi, however, achieving full traceability would be an enormous challenge. Chanthaburi specialises in high volume, low-value sales (treated sapphires change hands for as little as $2-3 per carat), and many transactions take place between traders with no common language, who haggle by typing numbers into a calculator.55 Bhattacharya, S., Chowdhury, A., Abid, A. A market like you've never sheen. The Hindu. 29th July 2017. https://www.thehindu.com/thread/arts-culture-society/a-market-like-youve-never-sheen/article19384978.ece (accessed 07th December 2021). Keeping a paper record of each gemstone sold, and passing chain of custody information on to buyers, would likely be an unachievable aspiration under these circumstances.

For governance mechanisms in the Thai coloured gemstone sector to successfully accommodate responsible sourcing, therefore, it may be necessary to consider schemes that do not require full traceability of stones. An alternative approach to supply chain mapping is explored in the subsequent section, A Chain of Confidence: A Pragmatic Approach to Traceability.

As discussed in the section A Growing Impetus For Governance, several large-scale mining companies have entered the coloured gemstones sector in recent years. Large-scale mining operations in developing countries can offer much-needed revenues for national budgets. To ensure that relations between large- and small-scale miners are well managed, effective governance is needed in which all stakeholders are represented.

Large-scale mining concessions can be granted in areas that are viable for small-scale mining or they can be granted in areas that only large companies can exploit, using specialist equipment and expertise. In either situation, large companies can face tensions with small-scale miners because in the latter case individuals may enter concession areas to pick over material rejected by the company, to find missed stones.

In some countries, finding a successful balance between the interests of large and small operators has proven to be challenging. In Mozambique, for example, the government has opened the ruby mining sector up to industrial, international mining companies. London-based Gemfields now operates a major mine in the country. The Mozambique authorities have deployed police forces to Gemfields’s concession area, to prevent trespass by artisanal mining groups,56Mozambique’s Ruby Mining Goes From wild West to Big Business. Bloomberg. 13 August 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-13/mozambique-s-ruby-mining-goes-from-wild-west-to-big-business (accessed 07th December 2021). and media reports have alleged a range of human rights and land rights violations by these police and by informal gangs of armed enforcers. Gemfields strenuously denies any form of sponsorship of informal security forces or culpability for the alleged actions of the police and describes reported gang activity as being between different groups of artisanal miners.

While no illegal behaviour by the company has been demonstrated, the allegations that have been made illustrate the social strife that has arisen in and around Gemfields’s concession area, since the company began operations,57 Valoi, E. The Blood Rubies of Montepuez. Foreign Policy. 03rd May 2016. https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/03/the-blood-rubies-of-montepuez-mozambique-gemfields-illegal-mining/ (accessed 07th December 2021). and highlight the fundamental tensions that can occur when large-scale and small-scale miners work in close proximity. For the Mozambican authorities, however, the formalisation of the sector has clear benefits. “The exploitation of rubies is contributing greatly to the revenue of the state. We are satisfied with that,” a local government representative commented to Bloomberg in 2018. In addition to taxes, ruby mining companies in Mozambique have provided other benefits that ASM miners would not, such as steady jobs, schools and local health clinics.58Mozambique’s Ruby Mining Goes From wild West to Big Business. Bloomberg. 13 August 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-13/mozambique-s-ruby-mining-goes-from-wild-west-to-big-business (accessed 07th December 2021).

We presented a similar story in a case study of Colombian emeralds, in another paper in this series Hands That Dig, Hands That Feed: Lives Shaped by Coloured Gemstone Mining. The arrival of large-scale mining, after the end of the Colombian conflict, brought many benefits. At the same time, informal mining was curtailed, as were the networks of emerald handlers that had grown up during the conflict, through which stones were passed in order to build and maintain alliances between groups. When peace came, many of the small-scale operators who had previously relied on emeralds for much-needed income were left without livelihoods.59Brazeal, B. Nostalgia for war and the paradox of peace in the Colombian emerald trade. The Extractive Industries and Society. Volume 3, Issue 2. Pages 340-349. April 2016. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214790X15000635 (accessed 07th December 2021).

As we also explored in that paper, however, effective governance can ensure that gemstone mining can peacefully include both large and small operations. Australia, for example, has developed a system of governance through which mining is accessible to individuals with pan and shovel just as much as it is to large companies. The rules governing the sector clearly signal what kind of mining is allowed where and what requirements there are for each mining method. This helps prevent confusion and disagreement over who has the right to occupy or mine any given deposit.60Hsu, T., Lucas, A., Pardieu, V. Gem Fossicking: Recreational Mining in Australia. GIA. 16th December 2016. https://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research/gem-fossicking-recreational-mining-australia. See also: Australian Opal Mining: A Model for Responsible Mining. InColor magazine. Issue 41. 2019. https://www.opal.asn.au/app/uploads/2019/01/InColor-41-Winter-2019-complete-22142.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

To foster healthy, sustainable gemstone mining sectors, governments must often adopt measures to help large companies and artisanal miners to co-exist. Examples of such include by ensuring adequate human rights training for the security forces that guard companies’ concession areas, by ring-fencing small-scale mining areas with proven reserves, as Australia has done, or by encouraging companies to institute support schemes for local independent miners. These could be schemes for the purchase of gemstones to feed into companies’ own supply chains, or technical assistance programmes and formalisation support programmes.61https://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/igf-asm-global-trends.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

Guidance resources are available for such endeavours. Organisations including the Responsible Jewellery Council,62Fritz, M., McQuilken, J., Collins, N., Weldegiorgis, F. Global Trends In Artisanal And Small-Scale Mining (Asm): A Review Of Key Numbers And Issues. January 2018. The International Institute for Sustainable Development. https://www.responsiblejewellery.com/files/Artisanal-and-Small-Scale-Mining-RJC-Guidance-draftv1.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). the International Council for Mining and Metals63Working Together. How large-scale mining can engage with artisanal and small-scale miners. IFC, The World Bank. https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/guidance/social-performance/artisanal-and-small-scale-miners (accessed 07th December 2021). and the World Bank64 CASM. Mining Together Large-Scale Mining Meets Artisanal Mining: A Guide for Action. March 2009 http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/148081468163163514/pdf/686190ESW0P1120ng0Together0HD0final.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). all provide high-level guidance on how large-scale mines can best engage with small operators – although some in the private sector describe these resources as primarily theoretical, and practically very challenging to implement on the ground for most companies, due to inherent legal, regulatory, financial, and reputational issues which they entail.65Based on discussions between TDi Sustainability and Coloured Gemstone Working Group members as part of the research process for this paper series.

By striving to ensure that large-scale and small-scale mining can co-exist, governments can realise a diversity of mining benefits: from large companies these include taxation revenues and structured community development projects, and from the artisanal sector a broad base of support to citizens’ livelihoods.

Over this series of six papers on coloured gemstone supply chains, we have explored the ways in which coloured gemstones affect people and places along their journey, both positively and negatively. We conclude our series by taking stock of some of the insights we have gained, about the underlying social and economic systems that make the coloured gemstone sector what it is, and we consider how these systems could evolve positively in future.

Retail companies are increasingly aware of social and environmental issues in their supply chains, and of the impetus from civil society to address these issues, where they exist. Meanwhile, retail customers increasingly desire coloured gemstones that come with clean environmental and social records (we explore these trends in detail in another paper in this series, A Storied Jewel: Responsible Sourcing And Retailing Of Coloured Gemstones).

Approximately 80% of coloured gemstones are produced through artisanal and small-scale mining,66 The World Bank. Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining. 21st November 2013. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining. See also: Shortell, P., Irwin, E. Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience. Natural Resource Governance Institute. May 2017. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/documents/governing-the-gemstone_sector-lessons-from-global-experience.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). and most of this mining takes place in developing countries in Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Latin America. As such, social and economic development is a keenly felt need for many miners of coloured gemstones, as well as for the networks of traders and manufacturers that they supply, and the communities in which they are based.

The responsible sourcing movement has emerged in order to benefit all three stakeholder groups: for customers to feel assured that their products do not carry the stigma of environmental or social harm; for retailers, large suppliers and processors to reduce their risks of reputation damage; and for developing world communities to benefit more from the goods they produce.

When responsible sourcing schemes are implemented with a strong focus on supply chain traceability, and on providing assurances that products are not associated with negative environmental and social impacts, they can be better suited to managing risk and reducing stigma, for retailers and customers, than they are to improving conditions for developing-world communities.

We discuss this phenomenon in the next two sections, starting with the illustrative case of the implementation of Section 1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Act, as it has valuable lessons for any future supply chain traceability scheme for coloured gemstones.

Effects of section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank act in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The United States introduced responsible sourcing legislation within the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, in 2010. Section 1502 of the Act states that companies must conduct due diligence on the tin, tungsten, tantalum and gold in their supply chains, and rule-making to support the Act identifies the OECD DDG as the framework through which this due diligence should take place.67Securities and Exchange Commission. Final Rule: Conflict Minerals. https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2012/34-67716.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). The OECD DDG itself stresses the importance of working constructively with entities further up the supply chain to improve conditions and mitigate risks, but the economic incentives for the companies that implement the guidance can be quite different. Working constructively with small entities in developing world locations is expensive, as is the establishment of the chain of custody systems that the OECD DDG recommends, in order to ensure traceability and identify human rights risks associated with supply chains in conflict-affected areas.

Reportedly, many US companies chose to simply stop sourcing tin, tantalum and tungsten from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on which the US legislation is focused. Switching to other supplier countries represented a faster and cheaper way to meet their legal compliance requirements and reduce operating risks.

As a consequence, according to a UN University study, poverty rates among artisanal miners in the Democratic Republic of the Congo rose markedly, leading to a 143% increase in child mortality in mining regions after the introduction of the US law.68https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/wp2016-124.pdf Although rights groups have claimed a reduction in funding for non-state armed groups following the legislation,69Ganesan, A. Testimony to the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee on African Affairs and Global Health Policy Regarding Dodd-Frank Section 1502. Human Rights Watch. 5th April 2017. https://www.foreign.senate.gov/download/ganesan-testimony-040517 (accessed 07th December 2021). a second academic study asserted that mining areas witnessed a sharp increase in low-level violence, due in part to the mass unemployment of former miners.70Stoop, N., Verpoorten, M., van der Windt, P. More legislation, more violence? The impact of Dodd-Frank in the DRC. Plos One. 9th August 2018. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0201783&type=printable (accessed 07th December 2021).

The assurance-inclusivity trade off

Eliminating an entire country from a supply chain may be the most striking example of the ways in which small and informal producers can be excluded from the global economy for the sake of companies’ reputations and customers’ peace of mind. However, it is not unique.

Professor Gavin Hilson, an expert in small-scale mining, wrote in 2016 of the difficulties of extending responsible sourcing schemes to the poorest producers, stating that “during a recent presentation, a pioneering Fairtrade jeweller conceded that reaching the informal, unlicensed mine operator in Africa was, indeed, exceedingly challenging, which is why most ethical mineral schemes and standards target ‘low hanging fruit”.

Professor Hilson quoted a Fairtrade official as saying in an interview: “Don’t go the artisanal route [which is] wild and uncontrollable” and expressing his scepticism “of running up the Bolivian Andes and the Amazon Jungle and finding a miner and saying, “this is Fairtrade” because it doesn’t work”.71Hilson, G., Hilson, A., McQuilken, J. Ethical minerals: Fairer trade for whom?. Resources Policy 49(2016)232–247 https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/portal/files/28192525/Ethical_Minerals.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021).

Instead, many schemes choose to work with small but well-organised producer groups that are already operating under relatively good environmental and social conditions, while legally registered and paying taxes; this enables them to provide assurances to retailers and customers about these producers’ practices. Reports indicate that this can be as much the case with coloured gemstones as it is will be with other products.72See, for example: Hilson, G. ‘Constructing’ Ethical Mineral Supply Chains in sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Malawian Fair Trade Rubies. Development and Change Volume 45, Issue 1. 2014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263346205_'Constructing'_Ethical_Mineral_Supply_Chains_in_Sub Saharan_Africa_The_Case_of_Malawian_Fair_Trade_Rubies (accessed 07th December 2021).

If a scheme offers assurances that products are not associated with environmental or social harm, then it typically employs a chain of custody system to trace where those products have come from. However, implementing chain of custody can be prohibitively expensive for many in the coloured gemstone sector.

A range of companies are currently developing technological solutions for chain of custody with small-scale coloured gemstone miners, using Blockchain-based approaches; however, the costs of implementation can be upward of US$ 500 per participant per month – plus more for the necessary hardware, and more still to provide environmental and social assurances of miners’ operations.73Cost estimate is accurate as of 2020, based on TDi Sustainability’s dialogue with multiple providers of Blockchain-based traceability solutions. This sort of cost is far beyond the reach of a typical artisanal miner of coloured gemstones, or even of a responsible sourcing scheme if it works with a large number of producers (for more information on the specific Blockchain technologies that are currently being applied to coloured gemstone supply chains, see the another paper in this series Glimmers in the Shadows: Perception and Reality in Global Coloured Gemstone Trading).

Broadly speaking, the more inclusive a chain of custody scheme is of poor, small-scale producers, the less assurance it can affordably provide. Assurance and inclusivity have a trade-off relationship. Moreover, when a lot of money is spent on chain of custody by retail companies or sustainability initiatives, less is available to foster positive social and environment impacts for producer communities.

Lowering the barriers to scheme participation

The chain of custody aspect of the responsible sourcing movement can play a key role in assessing where environmental and social issues exist within a company’s supply chain. A chain of custody can help to target efforts to address these issues and provide assurances to customers. However, such efforts must be balanced against the costs they incur in order to ensure that schemes are as inclusive as possible of the poorest producers.

Some responsible sourcing schemes adopt hybrid approaches to chain of custody, providing a pragmatic level of assurance to retailers and customers in those supply chains for which full chain of custody for each consignment of goods would be impractical. Fairtrade and the Better Cotton Initiative are two prominent examples of this approach.

Fairtrade applies a system known as mass balance for gold, cotton, cocoa, tea, sugar and fruit juices, which are often blended from multiple supply chains over the course of their production.74[1] Flocert. Mass Balance. FLOCERT website. https://www.flocert.net/glossary/mass-balance/ (accessed 07th December 2021).75Traceability in Fairtrade Supply Chains. Fairtrade International. https://info.fairtrade.net/what/traceability-in-fairtrade-supply-chains (accessed 07th December 2021). The Better Cotton Initiative adopts a similar approach for the cotton produced under its scheme.76Better Cotton. Better Cotton Standard System: Chain of Custody. Better Cotton Initiative. https://bettercotton.org/better-cotton-standard-system/chain-of-custody/ (accessed 07th December 2021).

Mass balance allows for certified and non-certified goods to be mixed, as long as the weights of the different types of goods entering the supply chain are recorded. A corresponding proportion of end products can then be sold with scheme labelling.

An approach based on product weight would not be a good fit for the coloured gemstone sector – a single 1-carat stone is a very different product from ten 0.1-carat stones. Nonetheless, the fact that mass balance is implemented for other commodities demonstrates that pragmatic alternatives to full chain of custody can be found, and can gain acceptance, when the complexity of a supply chain demands it. We explore what a pragmatic alternative to full chain of custody could look like for coloured gemstones in the next section of this paper.

For responsible sourcing to benefit poor producers, schemes must not only adopt a pragmatic approach to traceability, in order to keep the barriers to scheme participation low. They must also ensure that the environmental and social standards expected of scheme participants are achievable and foster genuine positive change. Schemes that offer a progressive approach to environmental and social performance, in which participants can start at modest benchmarks and work toward improvements, are well suited for this purpose. We discussed two such schemes, The Maendeleo Diamond Standards and The Impact Facility, in the earlier section of this paper Voluntary best-practice frameworks for the private sector.

A chain of confidence: a pragmatic approach to traceability

A pragmatic approach to supply chain traceability must follow prevailing best practices, for which a significant body of work exists for mined materials. The key global reference document on the subject is the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas77 OECD (2016), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Third Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/mne/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-Minerals-Edition3.pdf (accessed 07th December 2021). (the OECD DDG, described in the section Voluntary best-practice frameworks for the private sector). This guidance was created to address specific issues related to conflict financing and gross human rights abuses, but its approach is broadly applicable to a wide range of sustainability issues. It has at its heart the idea that companies should make reasonable efforts to investigate their supply chains, and to take steps to mitigate the risks that they find, either individually or collectively, with other companies in the sector.

The OECD DDG calls for participating companies to “establish a system … [for] chain of custody or a traceability system or the identification of upstream actors in the supply chain”,78Ibid. in order to identify, assess and respond to risks of negative impacts that may exist.

Given the highly complex nature of coloured gemstone supply chains (discussed in detail in another paper in this series, Glimmers in the Shadows: Perception and Reality in Global Coloured Gemstone Trading), TDi Sustainability believes that the best-practice expectations articulated by the OECD DDG can be met without the need for full chain of custody for individual stones. The OECD DDG states that “companies should take reasonable steps and make good faith efforts to conduct due diligence to identify and prevent or mitigate any risks of adverse impacts”,79Ibid. so small-scale miners, traders, lapidaries and retailers should not be compelled to adopt systems that would have an unreasonable negative impact on their ability to do business.

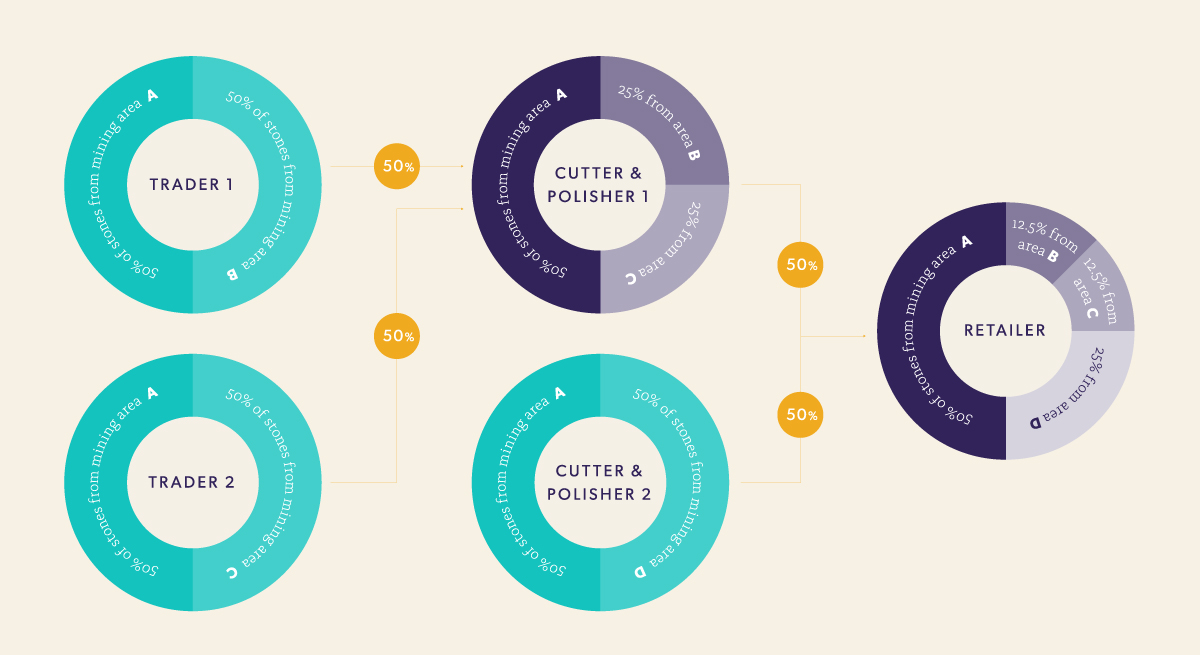

Rather than instituting a full chain of custody, in which the movements of each gemstone are tracked from hand to hand, an alternative system could be adopted in which each participant in the coloured gemstone supply chain estimates the percentage of total stock that originates in each mining region worldwide, either using his or her own professional knowledge or using data passed on by suppliers further up the chain. Such a system, explored below, would not provide a chain of custody for individual stones, but it could nonetheless represent a suitable traceability framework for responsible sourcing, and could give customers assurances that the companies from which they buy coloured gemstones are taking proactive steps to uphold human rights and environmental protections. Instead of a chain of custody, such an approach could be termed a “chain of confidence”.

The figure below illustrates the principle behind such a system.

Percentage-Based Chain of Confidence

In this figure, turquoise rings are for entities in the supply chain that estimate percentages for the origins of their gemstones themselves, based on their own general knowledge of their supply chain built up over their years in business. Purple rings are for entities that calculate estimated percentages for the origins of their gemstones based on the information passed to them by their suppliers. As such, any entity can start off a reporting chain for percentage-based chain of confidence. There is no requirement for hard data from informal mining and trading networks in cases when such data may be impractical to obtain.

The orange circles are for the percentage of the total stock of the entity on the right of the arrow that is supplied by the entity to the left of the arrow.

Of course, this is a highly simplified example for several reasons:

- In practice, each entity in the supply chain might source from dozens of suppliers, not just one or two.

- Geographic data on trading and processing would need to be passed, alongside geographic data on mining, using a similar percentage-based system.

- Most gemstones would pass through the hands of many traders, not just one.

- Supply chain entities are unlikely to fit neatly into the ‘dark blue’ or ‘light blue’ category. If such a system were implemented, then it’s likely that most supply chain entities would receive estimated percentages of gemstone origin from some of their suppliers but not from others and would have to estimate figures themselves for consignments from suppliers who did not give estimates.

However, the principles used in the figure above would not need to change, even for a vastly more heavily populated and nuanced supply chain: only the scale of the data collected would need to grow.

The data required for such a system fit well with the sort of pragmatic approach to supply-chain knowledge that is already practised by many traders of coloured gemstones. For example, Manraj Sidhu, an independent gemstone trader based in Tanzania who was interviewed for this paper, said, “we generally have a pretty good idea where the stones we source come from, even if we don’t know every single trader along the way, because we know the local geology”. Similarly, a number of luxury brands map and record the geographic regions from which their stones originate, in countries such as Sri Lanka, without keeping a detailed record of every miner and trader in their supply chain.80Based on interviews conducted by TDi Sustainability with supply chain experts at leading luxury brands.

The aspiration of such a system would be for companies, such as jewellery-makers and retailers to get a detailed, and reasonably accurate, picture of where their stones come from, and where they travelled, that could be verified further through spot checks; for example, through laboratory testing of sample sets of stones, or limited use of proof-of-origin techniques such as the Emerald Paternity Test (which is discussed in another paper in this series, Glimmers in the Shadows: Perception and Reality in Global Coloured Gemstone Trading).