Retailing

A Storied Jewel: Responsible Sourcing And Retailing Of Coloured Gemstones

Introduction

In the previous papers in this series we have followed the journey of a coloured gemstone, from the ground in which it was discovered, through the network of traders who bought and sold it, and through the hands of the craftspeople who cut it, polished it and set it into jewellery. We now complete its journey, as it arrives to its end customer.

For each person along the way the story of the stone has been different. For the miners who found it, the gemstone may have represented a way to pay a few days’ bills or – if it looked valuable – a step toward a better life. For traders, it may have been a puzzle that needed solving. A cloudy pebble in appearance, whose potential value could only be roughly guessed at, and which needed the right buyer to secure a good return. For the craftspeople who brought out the value from the stone, it might have represented a test of their skill, with a reward at the end for a job well done.

Now, in the retail world, the story of the stone changes again. It is an adornment, a symbol, and an artefact with history. For a customer, the story of that past might be compelling, romantic, exotic, and mysterious, or it might be disquieting, tarnished with thoughts of human suffering encountered along the way.

Customers do not buy coloured gemstones for their practical usefulness, as they would a washing machine or a car. Gemstone purchases are more focused on the story that the jewel tells – the story it carries within itself, and the story it helps its owner to tell about themselves.1Cracking the Coloured Gemstone Code. Accessed 17 November 2021. When the story is right, a gemstone can signal wealth, glamour, sophistication, beauty and taste. If the stone comes with social and environmental assurances around its production and processing it can even signal a conscientious and responsible nature.2Penelope Cruz Launches Sustainable Jewellery Collection with Swarovski. Accessed 17 November 2021.

While responsible provenance can enhance a stone’s story for its owner, that owner may not readily pay a price premium for it, and few retailers cite price premiums on responsibly sourced coloured stones as a motivating factor in their business. Many retailers genuinely want to ‘do the right thing’ within their supply chains, but a commercial rationale for responsible sourcing must also be found, if a for-profit company is to make corresponding changes to the way it does business. Often, this rationale is about the avoidance of loss – of reputation, competitiveness, and market size - rather than the anticipation of gains.3Statement based on several interviews between TDi Sustainability and CGWG members during production of these papers.

As we will explore in this paper, a product’s association with negative social and environmental impacts, in the public imagination, can cause customers to abandon one brand for another, or to forsake the product altogether if it is not essential to their lives (and coloured gemstones are not). Negativity can also cause regulators to become more involved in a product’s supply chain, introducing a costly compliance burden for companies.

Often, in part to avoid such losses, companies at the retail end of the supply chain will engage with voluntary schemes that certify their products, their sites, or themselves, against a set of standards for environmental and social responsibility. These schemes are typically developed by international organisations and industry associations in consultation with civil society. There has not been a strong drive toward certification in the coloured gemstone sector in recent years, compared to other goods, but change is now afoot, led by organisations including the Responsible Jewellery Council and the Coloured Gemstones Working Group and its Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform.

Whatever shape evolving schemes for responsible sourcing of coloured gemstones ultimately take, retailers’ bottom lines will remain beholden to the stories of impacts attached to their stones in the counties where they are bought, rather than the objective environmental and social impacts on the ground in the countries where they are mined, processed, and traded. Aligning stories in one part of the world with impacts in another is far from straightforward, and ultimately depends on greater knowledge and understanding of the issues at stake, by retail staff and customers alike.

We will walk through these issues in this paper. We focus primarily on the retail sector in the Western world because that is where most of the dialogue on responsible sourcing of coloured gemstones is currently taking place, but responsible sourcing should not be seen as a purely Western phenomenon. We hope that many of the insights drawn in this paper could be applied to nascent responsible sourcing movements in key non-Western markets including China and India, in due course.

Our White Papers are also available to download and read offline.

Please fill in your details to receive a download request.

Every year, retail customers worldwide spend around US$ 20 billion on coloured gemstone jewellery (not including sales of jade, which are very significant in the Chinese market).4The Coloured Gemstone Market Sparkles in 2017, London DE website, accessed 17th November 2021. That figure is only an estimate because - as with all other stages in the coloured gemstone supply chain - solid data on retail is hard to come by. However, it is an estimate that experts on the sector often use. About one third of this figure can be attributed to rubies, a quarter to emeralds and a quarter to sapphires. The remaining one-sixth of this figure accounts for all other coloured gemstones combined.

Coloured gemstones have experienced surging demand over recent years, with a new generation of younger customers who do not see the same singular allure in diamonds that their parents and grandparents did. People are looking for something new5The Coloured Gemstone Market Sparkles in 2017. London DE website. Accessed 17th November 2021.. Burmese sapphires and rubies have risen in value four-fold or five-fold since the early 1990s,62016 Tucson Gem Show, p7. Gemstone Forecaster. Vol 34, No 1, 2016. and other gems have enjoyed steep price rises too. Per-carat prices of ruby and emerald now surpass those of colourless diamonds.7Why are the Coloured Gemstones On the Rise and What are Consumers Looking for? Accessed 17th November 2021. As well-known gem types have grown more expensive, lesser-known gems have started to enjoy increased attention and market share as well, as buyers search for more affordable alternatives. Moreover, the growth trend for the coloured gemstone market is set to continue. One study predicts that global coloured gemstone sales will increase at 5.7% compound annual growth rate between 2021 and 2031.8Coloured Gemstones Demand Rising with Jewelry and Ornaments Industry Accounting for 85% Sales. Accessed 17th November 2021.

At one end of the coloured gemstone retail market there are large quantities of relatively low value stones, used to make everyday jewellery and decorative items. At the other end of the market are extremely rare, one-of-a-kind gems, that can sell for millions of dollars each. The Sunrise Ruby, a 25.6 carat gem from Myanmar, for example, sold for US$ 30.42 million in 2015.9Sunrise Ruby’ lights up the auction world. Accessed 17th November 2021. The Jewel of Kashmir Sapphire fetched US$ 6.7 million in the same year.10The $6.7 Million 'Jewel of Kashmir' and $5.2 Million 'Cowdray Pearls' Set Auction Records. Accessed 17th November 2021.

Rare and ultra-valuable gems are typically sold at auction, where their price is determined solely by the amount a buyer is willing to pay. More common gems are usually sold to end customers through shops, boutiques, and market stalls, at fixed or narrowly negotiable prices.

The diversity of jewellery itself is matched by a diversity of jewellery sellers. The famous names of the big jewellery brands might trip off the tongue but the figures for market share tell a different story. Branded jewellery could only lay claim to an 18% market share in 201911Le Vian Introduces the Newest Gem on Earth As Demand for Colored Gemstone Jewelry Grows. Accessed 17th November 2021. (though it is growing).

The size of big brands’ market share is important for responsible sourcing. The big brands in any industry are typically subject to more public scrutiny than their smaller counterparts12Shaming the Corporation: The Social Production of Targets and the Anti-Sweatshop Movement. Tim Bartley and Curtis Child, American Sociological Review, Vol 79, Issue 4. 27th June 2014. and, at the same time, have more resources at their disposal for activities that are not directly concerned with profit-making. They can play leadership roles to encourage positive change in their industries overall. As such, an industry with few big brands is an industry with weaker drivers for change.

Branded jewellery’s market share is predicted to rise to 25%-30% by 2025, and the market opportunity is especially attractive for coloured gemstone retailers.13Le Vian Introduces the Newest Gem on Earth As Demand for Colored Gemstone Jewelry Grows. Accessed 17th November 2021. According to one study, coloured gemstones offer retailers average margins of 65%, compared to 33% for diamonds.14Coloured Gemstones Capture More Consumer and Trade Attention. Accessed 18th November 2021. If major coloured gemstones brands make gains, both in developed and developing markets, and play a leadership role in combatting ethical issues throughout the supply chain, then this could represent one important route to realising responsible sourcing goals in the industry overall. Where big brands go, smaller companies tend to follow in time. As discussed in the section Ethical Conundrums: “avoiding bad” or “doing good”? this is a path that must be treaded carefully, however, if small, independent participants in the coloured gemstone sector are not to be marginalised or excluded.

Synthetic Gemstones in the Retail Sector

Since the late 1800s, laboratories have been growing coloured gemstones that imitate those formed underground by natural geological processes. Most synthetic gemstone materials are used in industry – for electronics, lasers, and other applications. But synthetic gemstones are also used to make jewellery, sometimes for a fraction of the price of natural stones. Rubies and sapphires, in particular, can be synthesised very cheaply. According to Matthias Krismer, a procurement manager at Swarovski interviewed for this paper, “A synthetic one carat ruby produced using the Czochralski process would typically cost in the region of US$ 200 to US$ 300. A similar-looking treated one carat ruby mined in Burma, free of inclusions to the naked eye, might sell for ten times that amount. A high-quality natural one carat Burmese ruby, without any treatments, could sell for up to US$20,000”.

While synthetic gemstones may be cost-effective, their appeal is far from universal. Professional Jeweller, a UK jewellery magazine and website, interviewed a range of experts in June 2019 and found them to be unanimous in their opinion that synthetic gemstones would never replace natural stones. Stefan Reif, director of the International Coloured Gemstone Association, commented to the organisation that “no technology could replace the magic and fascination of natural coloured gemstones.”

Accordingly, synthetic gemstones are strictly regulated. Bodies such as the Federal Trade Commission in the US have very specific guidelines for how a synthetic gemstone can be described by sellers, to avoid any confusion with natural stones. CIBJO, the world jewellery confederation, also publishes detailed guidelines, through its series of authoritative “blue books” for the industry.

From a responsible sourcing perspective, synthetic gems present a conundrum. They bypass the early stages of the supply chain (mining and most of trading, which are described in papers 2 and 3 in this series respectively), and are simply cut, polished, and set into jewellery pieces for retail.

This means that sellers of synthetic gems can confidently assert their “conflict free” status and can rightly claim that their stones are free from virtually all negative supply chain issues typically associated with natural stones.

At the same time, however, synthetic stones provide far fewer positive impacts for developing world communities, since their production does not generate livelihoods for the miners and networks of traders that the production of natural gemstones does.

The ethical implications of synthetic gemstones are, therefore, not straightforward. For more discussion on this topic see the subsequent section, Ethical Conundrums: “avoiding bad” or “doing good”?

Trading Near Mine Sites

The meteoric rise of online retailers over the past quarter century, such as Amazon, eBay and Alibaba, has brought about a fundamental evolution in the way people shop for goods and services. Transactions that would previously have taken place on the high street are now carried out with clicks and scrolls in customers’ living rooms, and the scale of change is profound. In February 2019, online sales volumes in the United States surpassed those of general merchandise across all physical retail outlets.15Online shopping overtakes a major part of retail for the first time ever. CNBC. Accessed 18th November 2021.

Online jewellery sales, meanwhile, have lagged far behind those of other goods. A report by McKinsey and Company estimates that online jewellery sales make up only 13% of the overall market, predicted to increase to 18- 21% by 2025.16State of Fashion: Watches and Jewellery. McKinsey. Accessed on 18th November 2021.

The 2020-21 COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruption to the coloured gemstone retail sector, due to the shuttering of shops, the cancellation of trade fairs and other logistical constraints. However, customer demand has remained buoyant.17The Future of the Jewellery Industry: Trends and Insights. Matter of Form. Accessed 16th November 2021. Some jewellery retailers see commercial opportunities within the shift toward online sales, accelerated by the pandemic, and are experimenting with new sales models to capitalise on these opportunities. The British jewellery retailer Serendi, for example, has launched an online-only platform on which customers can view unique high-end coloured gemstones, and design their own bespoke jewellery incorporating these stones. Serendi asserts that all the gemstones they sell are fully certified and responsibly sourced.18Serendi website.

As noted by the branding consultancy Matter of Form, “customers will, and do, purchase jewellery online: the key is creating a seamless customer journey that conveys the storied history of each piece”.19The Future of the Jewellery Industry: Trends and Insights. Matter of Form. Accessed 16th November 2021. Increasingly, responsible sourcing considerations play a key role in this storytelling.

Gemstones’ value can vary widely over time. In part, this is because their value is determined solely by their perceived allure. Gemstones are not transformed by industry in order to make things, like iron is to make steel, and they are not necessary to sustain life, like food products are. Gemstones can go in and out of fashion in ways that essential commodities cannot.

Gemstones’ allure to potential buyers can be related to several factors. The online auction house Catawiki, for example, characterises the value of gemstones as follows:20What determines the value of a gemstone? Catawiki website. Accessed 18th November 2021.

- Durability: The stone’s ability to last the test of time. Rubies and sapphires are considered particularly durable stones.

- Rarity: Stones that are special, unusual, or ‘one of a kind’ are often highly sought after.

- Acceptability: Fashion trends, or the cultural and spiritual significance attached to certain stones.

- Beauty: The subjective aesthetic appeal that a certain stone has, which is unique for every customer.

Catawiki is a general-purpose auction site and its breakdown of the components of a gemstone’s value are not seen as authoritative by professional gemstone traders. Nonetheless, they are insightful. They contrast with the “four Cs” of gemstone grading, which are widely recognised and used within the trade: cut, colour, clarity, and carat.21Judging Quality: The Four C’s. Pala International website. Accessed 18th November 2021. Catawiki’s criteria for gemstone value indicate that, at the retail level, these technical characteristics from the trade give way to more subjective aspects of a gemstone’s allure, and to the emotional effect the stones can produce in customers.

This subjectivity can lead to large fluctuations in price. For example, a one carat navy blue Ceylon sapphire that sells for US$ 1,000 in Europe might fetch US$ 2,000 in Korea or Thailand, due to Asian buyers’ preference for relatively darker shades.22Sapphire Shop. Raymond H. Lopez and Jeff Dannels. Lubin School of Business Case Studies, Pace University. 2nd January 2007.

A stone’s origin (or believed origin) has the potential to significantly affect its allure. A sapphire from Kashmir might fetch a price many times higher than a comparable sapphire from Madagascar, for instance.23Governing the Gemstone Sector: Lessons from Global Experience, p6. Natural Resource Governance Institute. Accessed 18th November 2021. Similarly, a very high-quality unheated Burmese ruby might sell for US$ 1 million a carat, while a comparable Thai ruby would command a tenth of that price.24The Coloured Gemstone Market Sparkles in 2017, London DE website. Accessed 18th November 2021.

These price differences arise from the relative prestige of gemstones from different locations, rather than from responsible sourcing considerations. Within the four characteristics listed above, ‘origin’ could be viewed as part of the rarity and acceptability of gemstones.

Rarity and acceptability could also cover the price differences between treated and untreated gemstones. A coloured stone that has undergone heating or other treatments to bring out its colour is a more commonplace and less appealing item than a gemstone whose brilliance was wrought solely by geological forces over millions of years.

As noted in the previous section, when treatments are disclosed they can affect the price of a gemstone by a factor of around ten.25Interview with Matthias Krismer, procurement manager at Swarovski. September 2019. However, treatments are rarely disclosed. According to Roland Naftule, a vice-president of CIBJO, in an interview for this paper:

Except for a few high-end retailers there has been very little progress in recent years to disclose gemstone treatments to customers. We’re basically at the same non-disclosure level to the consuming public now as we were back in the 1970s and 1980s. More gemstones are treated today than ever before. Well over 90% of rubies and sapphires sold today at the retail level are treated, and over 97% of emeralds, and large numbers of other gemstones too.26Interview conducted in August 2019.

Coloured Gemstone ‘Provenance’

For the rest of this section we will discuss the idea of ‘provenance’, and how it relates to coloured gemstone retail. Provenance, in the sense in which we use it here, is distinct from ‘origin’ and concerns the ethical, social and environmental narrative around a gemstone’s journey from the ground to the end customer. It encapsulates the perceived impacts to people and planet associated with the stone’s extraction, trading and processing.

Customers today are unquestionably more aware of issues surrounding gemstones’ provenance than they were ten or twenty years ago. A 2021 market research study, for example, found that 79% of purchasers of coloured gemstones considered knowledge of how workers at mines and cutting factories are treated to be “somewhat important” or “very important” to them.27Coloured Gemstones Capture More Consumer and Trade Attention. The MVEye. Accessed 18th November 2021. However, the ways in which provenance affects retail are complex.

Campaigning organisations such as Human Rights Watch state that the retail choices of customers can create pressure for companies to adopt responsible sourcing practices. Speaking about jewellery in general, rather than coloured gemstones specifically, the organisation said in a 2018 report that “consumers increasingly demand responsible sourcing”.28The Hidden Cost of Jewelry. Human Rights Watch. 8th February 2018. Accessed 18 November 2021.

Other observers downplay the importance of responsible sourcing in customers’ purchasing choices. For example, James Cashmore, a supply chain expert, relayed to the Guardian newspaper in 2014 that “For fashion and jewellery, aesthetics are always paramount so it’s only when the style and fit are right, that ethics come in to play”.29Consumer behaviour and sustainability - what you need to know. The Guardian. Accessed 18th November 2021. At a 2019 seminar held in London for jewellery retail staff, hosted by the coloured gemstone company Gemfields, staff from across the retail sector, from a range of companies, relayed that customers rarely, if ever, asked questions about provenance, certification or ethics, but also that that their head offices did not provide detailed staff training or information that would allow them to adequately discuss provenance and certification with customers if such questions were asked.30Interview with Jack Cunningham, Group Sustainability, Policy and Risk Director, Gemfields Ltd. October 2019.

No market studies have yet been published which could shed light on whether a gemstone’s provenance can significantly affect its retail value, so the question of whether or not, statistically speaking, a responsibly sourced gem can command a price premium remains unanswered.

Studies that have been conducted in other sectors suggest that the effect of responsible provenance on price is limited. The coffee sector, although not highly analogous in structure to the coloured gemstone sector, offers some evidence in this regard. A 2005 study of Fairtrade coffee in the Journal of Consumer Affairs states that “a substantial number of surveys showed that consumers value the ethical aspect in a product. However, consumers’ behaviour in the marketplace is apparently not consistent with their reported attitude toward products with an ethical dimension.” Another paper, published by the MIT Political Science Department in 2014, found that the Fairtrade label boosted coffee sales by almost 10%, provided the price did not change but that, when a price premium was introduced, consumers’ willingness to pay extra for this labelling became very uneven.31Consumer Demand for the Fair Trade Label: Evidence from a Multi-Store Field Experiment. Jens Hainmueller, Michael J. Hiscox, Sandra Sequeira. Harvard Business School. February 2014. Accessed 18th November 2021.

In the public imagination, perceptions of the provenance of gemstones, and other goods, are more frequently shaped by reported negative impacts that they are by the benefits of a sector for its participants. Such perceptions in the jewellery sector have been driven by high profile activist campaigns, from the late 1990s onward. In 1998 the campaigning group Global Witness released the seminal report A Rough Trade, describing how diamonds helped fuel the Angolan civil war.32A Rough Trade. Global Witness. 1st December 1998. Accessed 18th November 2021. The film Blood Diamond followed in 2006, as have multiple civil society reports and initiatives dealing with ethical issues in gemstone supply chains over the last two decades – both for diamonds and for coloured stones. To give a few examples: a 2013 briefing by World Vision “Behind the bling: Forced and child labour in the global jewellery industry,”33Behind the bling: Forced and child labour in the global jewellery industry. World Vision. 2013. Accessed 18th November 2021. https://www.worldvision.com.au/docs/default-source/school-resources/jewellery-industry-factsheet.pdf details multiple ways in which workers involved in mining gemstones and manufacturing jewellery are vulnerable to exploitation; two recent reports by Global Witness, “Jade: Myanmar’s “Big State Secret”” and “War in the Treasury of the People: Afghanistan, Lapis Lazuli and the Battle for Mineral Wealth,” allege gemstones’ role in the funding of military ruling elites and non-state armed groups such as the Taliban;34Jade: Myanmar’s Big State Secret. Global Witness. 23rd October 2015. Accessed 18th November 2021; War in The Treasury of The People: Afghanistan, Lapis Lazuli and The Battle For Mineral Wealth. Global Witness. 5th June 2016. Accessed 18th November 2021 and the 2018 report by Human Rights Watch “The Hidden Cost of Jewellery”35The Hidden Cost of Jewelry. Human Rights Watch. 8th February 2018. Accessed 18th November 2021. publicly scrutinises 13 major jewellery companies’ attempts to address human rights risks in their diamond and gold supply chains, against burgeoning international standards, and is sharply critical of most of their efforts.

Campaigns like these are made possible by the globalisation of information. Information technology allows descriptions and images of the living conditions of poor and sometimes desperate communities in remote regions of the world to be gathered, compiled and woven together into compelling narratives. The same information technology allows civil society organisations to get their messages out to a worldwide audience, and to mobilise support for their cause. 36Responsible Sourcing Takes Hold In The Jewelry Industry. Forbes. 17th October 2016. Accessed 18th November 2021. As the power of information technology to connect the world’s people grows ever further, the emotive power of such supply chain narratives is likely to grow too.

Customer concerns over supply chain ethics may be particularly strong in the jewellery sector. As the then chief executive of the Responsible Jewellery Council, Michael Rae, put it in 2013, jewellery “is beautiful and finely crafted, but really people buy jewellery because of what it represents – the best of human emotion … If you are trying to sell a product that represents the height of human emotion, you do not want that associated with collateral damage."37Is the Responsible Jewellery Council an imitation ethical standards body?. The Guardian. 11th June 2013. Accessed 18th November 2021.

With little prospect of price premiums for responsibly sourced stones, and ample risk of bad press, coloured gemstone retailers’ commercial motivations for engaging with responsible sourcing (i.e. those motivations that lie beyond the simple ethical imperative to ‘do the right thing’) are more often about the avoidance of loss than they are about the anticipation of gains. Association with negative social and environmental impacts can significantly affect a brand’s sales, and can even depress whole industries, reducing purchases across the board, as has happened to diamonds in recent years. Several commentators have linked weak diamond sales to negative publicity around “blood diamonds”38For example: “Diamonds Aren't Forever: Millennials Turn Their Backs on 'Unethical And Expensive' Gems”. The Independent. 30th September 2016. Accessed 18 November 2021., with Marie Driscoll, the managing director of luxury and fashion at an international research and advisory firm, commenting to an industry magazine that “a consumer can turn away from a brand for the rest of their life if they think they see a blood diamond. And the fact that the industry isn't coming together and being more transparent and calling out bad players hurts the whole industry”.39Rock bottom: Tracing the decline of diamond retail. Retail Dive. Accessed 18th November 2021. A senior public relations expert who specialises in the jewellery sector also highlighted the risks for brands that do not engage in responsible sourcing, when interviewed for this report: “millennials who are interested in responsible sourcing will often research online before shopping, and will base their choice of shops to visit on the ethical credentials on their websites.”40Interview given anonymously in May 2019.

In addition to these commercial considerations, companies that deal in coloured gemstones may be motivated to engage with responsible sourcing pre-emptively, lest the industry attract sufficient pressure from civil society and governments for responsible sourcing legislation to be introduced, imposing a costly compliance burden. The possibility of supply chain governance regulation for the jewellery industry in the US was raised by the Department of State in April 2019, to combat money laundering and conflict financing,41State Department Warns of Coming Jewelry Industry Crackdown. JCK Online. 16th April 2019. Accessed 18th November 2021. 42U.S. Department of State Calls for Greater Jewelry Supply Controls. JCK Online. 9th August 2019. Accessed 18th November 2021. and responsible sourcing legislation was enacted recently in the gold, tin, tungsten and tantalum industries. The US43Final rule pursuant to Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Securities and Exchange Commission. 22nd August 2012. Accessed 18th November 2021. and the EU44Regulation (EU) 2017/821 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Official Journal of the European Union. 19th May 2017. Accessed 18th November 2021 introduced regulations in 2012 and 2017, respectively, to compel companies that used these minerals to address conflict and human rights issues in their supply chains.

Summing up the information presented in this section, issues around gemstone provenance can affect retail in four ways: they may have a modest effect on the price a customer is prepared to pay, if other conditions are right; they can affect a brand’s favour with customers in comparison to its peers; they can affect gemstone sales overall, across the board; and they can lead to legislation and compliance requirements if not addressed voluntarily.

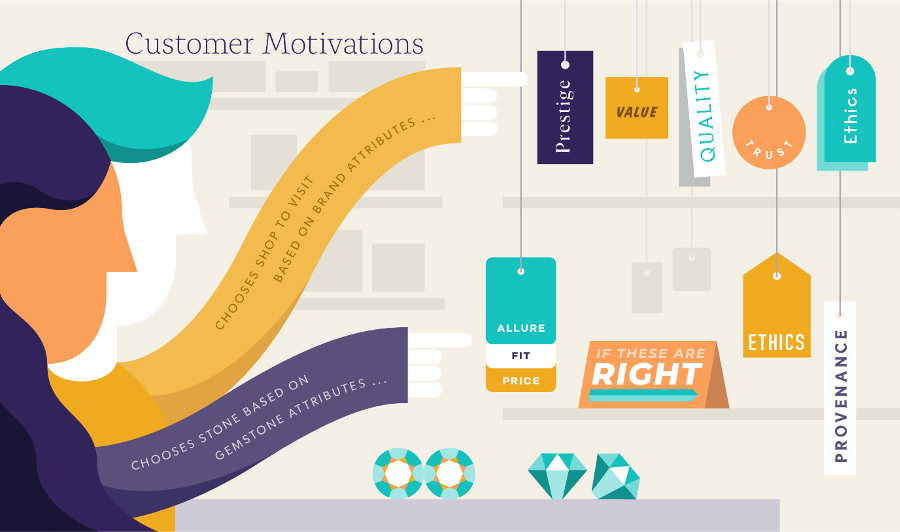

Figure 1 visualises some of the traits described in this section, showing how an individual customer’s decision-making process might look, and demonstrating the two different routes through which retail outlets might see provenance affect gemstone sales.

Figure 1: A possible framework for understanding customer motivations when shopping for coloured gemstones

As discussed in the previous section, perceptions of provenance issues in the jewellery sector tend to be shaped by high profile reports by rights groups, which focus on combatting the most egregious negatives present in supply chains – such as child labour, forced labour, conflict funding, and gross environmental abuses.

From the perspective of an advocacy organisation, calling out the worst practices, and demanding change, is the right thing to do. At the same time, from the perspective of a retail customer, making the purchasing choice that guarantees negative issues are avoided may not, necessarily, be the overall best thing to do. Minimising the bad is not the same as maximising the good.

To explain this statement; if a huge trove of gemstones of all types and sizes were somehow discovered that could supply the entire world market, then all negative social and environmental impacts of gemstone mining could cease. But, at the same time, hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of workers with few other ways to gain an income would find themselves without livelihoods. Livelihoods which, in the vast majority of cases, workers freely choose because they represent the best option they have for themselves and the people whom they support, no matter how arduous they might be. It follows that choosing gems that can be assured as free from social and environmental harm is not always intrinsically or categorically the most ethical course of action for a retail customer. Unless a supply chain is fuelling civil conflict or is associated with egregious human rights issues such as the worst forms of child labour or modern slavery, producers and their communities are generally better off with market access than without it.

A natural, conscientious reaction to the existence of severe social and environmental impacts associated with raw material production and processing is to seek to build fully traceable supply chains, which can be assured as ‘free from’ harm.45See for example the 2016 report by the European Parliament calling for the ‘creation of a certified ‘abuse-free’ product label at EU level’: “Report on corporate liability for serious human rights abuses in third countries”. European Parliament. 19th July 2016. Accessed 18th November 201. Yet there is a body of literature that argues that by cleansing supply chains of negative issues, initiatives can exclude those small producers and processors who are most in need of the income that their participation in the supply chain brings.

This holds true in the coloured gemstone sector. According to Charles Abouchar, the President of the CIBJO Coloured Stone Commission, “our dilemma has always been how to satisfy the demands being made by consumers, civil society, compliance organisations and, increasingly, by some of the larger jewellery retailers, without the unintended consequences of eliminating large groups of innocent participants in our industry.”46Special Report: Coloured Stone Comission. CIBJO. Accessed 18th November 2021 Stuart Robertson of GemWorld International, a private company specialised in gemstone pricing, expressed similar concerns in an industry press article, that “efforts at ethical sourcing [have the potential to] simply put the vast majority of small-scale folks out of business for lack of resources to meet requirements that have little to do with the actual integrity of the production.”47Analysis: The State of the Coloured Stone Market. National Jeweler.

Any future certification scheme for responsibly sourced coloured gemstones must ensure that participation costs are not beyond small producers’, traders’ and manufacturers’ means. The implementation of a scheme’s environmental, social and governance controls costs money, and that cost must be borne at some point in the supply chain. One reason that poor, small scale producers, traders, and manufacturers stay poor is their relative lack of power compared to other supply chain participants, who can drive down prices and pass on costs. In a supply chain where power imbalance is not addressed, therefore, certification schemes can become one more cost for smaller entities to bear – or risk losing market access by refusing.48See, for example, “Limitations of Certification and Supply Chain Standards for Environmental Protection in Commodity Crop Production.” Waldman and Kerr. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 6:429–49. 2014.

Making retail purchasing choices in line with certification schemes is an important component of responsible sourcing, but schemes are most effective when they are focused on including, and doing good for, those in the supply chain who are most in need, and not simply geared to “avoiding the bad” for end customers. The claims of positive impacts made by a certification scheme, or a brand, should be given just as much weight, and scrutiny, as claims that are made on the avoidance of harm. We explore these issues further in the final paper in this series Letting it Shine.

Certification schemes with associated product labelling are well established for many everyday items: Fairtrade coffee, Marine Stewardship Council certified fish, and Forest Stewardship Council certified wood, to give a few examples.

Gold and diamonds, too, have product-label certification schemes. The Fairtrade mark has been applied to gold, as has the similar initiative, Fairmined, giving customers assurance that specific ethical standards have been met for the gold in front of them at point of purchase. The diamond sector, similarly, has the Maendeleo Diamond Standards, a system newly launched in 2019 to certify artisanal and small-scale diamonds as ethically mined.49DDI Launches Maendeleo Diamond Standards: A proven system for ethical artisanal and small-scale diamond mining”. Diamond Development Initiative press release. 24th April 2019. Accessed 18th November 2021. The diamond sector also has the Kimberley Process, which grew out of public backlash over ‘blood diamonds’ in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Producer country authorities participate in this process in order to certify rough diamonds as being conflict free, and an accompanying System of Warranties allows retailers to declare individual cut stones as conflict free to customers.

A customer shopping for coloured gems will find no such labels on their stones. The ways in which coloured gemstone mining and trading are structured (described in previous papers in this series -Hands that Dig, Hands that Feed; and Glimmers in the Shadows-make product labelling uniquely challenging. Stuart Pool, founder of ethical gemstone suppler Nineteen48 commented to the BBC in 2018 that in the jewellery sector in general “it’s almost impossible to discover where anything has come from. It all gets put into a big pot and mixed together.” He relayed that coloured gemstones are especially challenging for certification; “they come from dozens of different countries and each has its own economic and political situation,” … “You’ve got massive disparity which makes it hard, if not impossible, to implement a global solution.”50The Rise of Guilt-Free Gems. BBC Culture. 19th December 2019. Accessed 18th November 2021.

The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) extended its Code of Practices, which previously had been focused on precious metals and diamonds, to emeralds, rubies and sapphires in April 2019. However, due to the Code’s complexity it is not well suited to small and informal miners and traders, which make up by far the greatest proportion of businesses in the sector.51Statement based on interviews between TDi Sustainability and CGWG members during production of these papers.

Companies that participate in RJC assessment can gain certification for ethics, human rights, social and environmental performance, and responsible sourcing practices. The latter aspect of the Code of Practices is discussed in the final paper of this series, Letting it Shine. The RJC Code of Practices certification assures the business practices of a company overall, and does not translate to labels on stones to assure customers of their provenance.

Eight luxury brands and gemstone mining companies have come together to form the Coloured Gemstones Working Group (CGWG) to catalyse positive change in the coloured gemstones industry by promoting responsible operating and sourcing practices. The CGWG supported this series of expert papers, and has also developed a comprehensive set of learning resources and tools that is specially designed to encompass all types of gemstones and all sizes of operators. These resources and tools are housed on the Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform,52The Gemstones and Jewellery Community Platform. an open access online portal launched in April 2021 with the purpose of promoting learning and capacity-building through free access to information and training material. The portal supports the implementation of responsible sourcing and due diligence programs across gemstones supply chains. It also includes a community component, linking suppliers and buyers with shared sustainability objectives. While the Gemstone and Jewellery Community Platform process can make responsible sourcing more accessible to small operators, it does not act as a certification scheme and, like RJC certification, it too does not translate to labels on stones.

Should a product labelling scheme for coloured gemstones emerge in future (and we discuss ideas for such a scheme in the final paper in this series, Let it Shine) the manner in which it is presented to retail customers will be of key importance. As noted in the previous section, for a scheme to be effective it should be as focused on doing good for those in the supply chain who are most in need, as it is on “avoiding the bad” for end customers. It should also harness the storytelling potential of coloured gemstones, in order to ensure strong uptake by retail customers.

According to James Cashmore, a supply chain expert, “many brands use rational/corporate language and concepts when talking about sustainability, when what they need to do is think about creating consumer advocacy by building much stronger emotional connections.”53Consumer behaviour and sustainability - what you need to know. The Guardian. 10th September 2014. Accessed 18th November 2021.

This sentiment can be applied to sustainability labelling, and coloured gemstones are uniquely well suited to emotional storytelling. They are exotic, their formation over eons under the earth imbues them with mystique, and the far-flung locations from which they are sourced adds to their romance. A compelling and truthful tale of responsible provenance, woven in, can add a powerful new dimension to the storytelling narrative. If this narrative can be incorporated into a certification scheme then it could potentially drive much-needed customer uptake of responsibly sourced stones.

Moreover, such a scheme could potentially have traction in emerging markets, as well as in traditional gemstone-purchasing countries. A 2012 study by McKinsey & Company forecast strong growth in the importance of “emotional considerations” for Chinese consumers’ buying choices – in particular, according to the study, “whether a product reflects the user’s sense of individuality”.54Meet the 2020 Chinese Consumer, p28. McKinsey & Company. March 2012. Accessed 18th November 2021. Purchasing responsibly sourced jewellery can make a strong statement about an individual’s sense of compassion and conscience and, with China already accounting for 32% of luxury purchases globally, even a small increase in Chinese demand for responsibly sourced gemstones could have enormous effects on the market overall.55China Luxury Report 2019, p5. McKinsey & Company. April 2019. Accessed 18th November 2021.

Customers’ expectations are rising for supply chain responsibility. Whether or not customers are prepared to pay extra for assurances of responsibility is uncertain but, in a competitive market, retailers must try to meet customer expectations nonetheless - or risk losing out to competitors who can.

Retailers that rise to this challenge must do so while also meeting customers’ other expectations, for more classical gemstone and jewellery attributes such as a piece’s allure, its fit with the purpose that the customer wants it for, and its price (see Figure 1, above). To make an attractive piece of jewellery, craftspeople must typically bring together many different stones, from diverse corners of the world — often of many different gem varieties. Unless the jewellery maker is prepared to limit himself or herself to a few repetitive patterns, they will inevitably have to bring together stones whose provenance stories are very different from each other’s. Some may come with responsible sourcing claims attached to them, and others will not. Some may have come from Australia, and others from Afghanistan, while others’ origins may be completely unknown. Some may be treated, some untreated. Some artisanally mined, and some industrially mined, or even lab grown.

It is extremely challenging under these circumstances for jewellery retailers to design simple, effective marketing messages that accurately represent the complexities of the sourcing environment that they are faced with. Yet studies have shown that customers’ attention is increasingly hard to attract to marketing material, and that simple messaging is vital for competitiveness.56The Rising Cost of Consumer Attention: Why You Should Care, and What You Can Do About It, Harvard Business School. 17th January 2014. Accessed 18th November 2021.

The task of simple, effective messaging is made all the harder by the fact that there is no overall public consensus on what ‘responsibly sourced’ really means. According to one study, for example, UK customers are predominantly interested in the environmental impacts of the products they buy, while US customers are predominantly interested in social and governance aspects.57Cost remains principal driver for young consumer behaviour. Innovation Forum. 21st June 2019. Accessed 18th November 2021. So two customers might disagree on whether a product is sourced responsibly, even when they both know the full facts about its provenance. By focusing on one aspect of responsible sourcing over another, companies risk alienating portions of their customer base.58Consumer behaviour and sustainability - what you need to know. The Guardian. 10th September 2014. Accessed 18th November 2021.

The challenges do not even end when a retailer has settled on a concept of responsible sourcing that resonates with their customer base. Many retailers are hesitant to introduce responsible sourcing labelling to their display cabinets because they fear that the remainder of their gemstones and jewellery will be tarnished by comparison. Their concern is that if some pieces are described as ‘responsible’, customers will assume that all the others were sourced irresponsibly.59Interview conducted with Sarah Carpin, Director of Facets PR, for this report.

Moreover, academic research indicates that building a strong reputation for corporate responsibility does not help to shield companies from activist pressures. In fact, the opposite may be true. According to one study,60Good Firms, Good Targets: The Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility, Reputation and Activist Targeting. King, Braden and McDonell Mary-Hunter. January 2015. Accessed 18th November 2021. firms that invest heavily in building their reputation for responsibility are, in turn, held to higher standards than their peers, and disproportionately targeted by activist organisations. The fact that these firms have committed to high ethical standards makes any shortfalls in corporate responsibility more conspicuous, and supplies the organisations that campaign against them with increased public attention.

Customers, naturally, want to make clear ethical choices about their purchases, and want to be assured that the items they buy are not causing harm somewhere in the world. But, for jewellery retailers, fulfilling these customer expectations, and promoting genuinely responsible supply chains, while remaining commercially competitive, can be very challenging. Companies are ultimately beholden to the purchasing habits of their customers, so customer behaviour – just as much as corporate behaviour – shapes the ethical landscape of gemstone sourcing. As noted in the section Customer Values And Expectations For Coloured Gemstones many retail staff do not feel adequately equipped with knowledge to explain the complexities of provenance to their customers. This means that staff cannot effectively advise customers on responsible sourcing, and help to shape their purchasing behaviour. Therefore, opportunities may be missed to guide coloured gemstones toward a more sustainable future. Through staff training, retail companies can help to address this shortfall.

The retail sector for coloured gemstones is about emotion, and about stories. Those stories can be good or bad, but either way they shape the value of the stones that are sold. Increasingly, questions of supply chain responsibility are woven into these stories.

Coloured gemstone sales are not dominated by big brands, in the way that many other products are. The big brands in any industry typically play a leadership role in raising standards for responsible corporate behaviour, introducing practices that smaller firms then follow. So, for change to come about in the coloured gemstone sector, creative collaborations between industry players, associations and other entities may be needed.

There is little evidence to suggest that customers, by and large, will pay a price premium for responsibly sourced stones, yet retailers have a commercial incentive to source responsibly, nonetheless. For retailers, responsible sourcing can be less about the anticipation of gains as it is about the avoidance of loss; bad press and NGO censure can cause customers to abandon one brand for another, or turn off a product entirely. They can also lead to costly compliance requirements being imposed by regulators.

Customers may find solace in labelling schemes that offer assurances their supply chains are free from specified social and environmental ills but disassociating supply chains from negative issues is not the whole answer. Avoiding the bad is not the same as doing good. When retailers do not source from challenging geographies, or when they require environmental, social and traceability standards that small operators cannot meet, the people who are in the direst need of gemstone income can be shut out from the sector.

Retailers are beholden to the purchasing habits of their customers and must ultimately give customers what they want if they are to remain commercially competitive. In the field of responsible sourcing, they are faced with the challenge of distilling their programmes and efforts into simple and accessible marketing messages, which interweave with the stories that customers want their gemstones to tell.

To ensure that these stories are aligned with best practices, which will create the greatest good for people and planet throughout the supply chain, education and understanding are key. Retail companies should examine their existing efforts to train shop-floor staff in responsible sourcing issues, and strengthen training where needed. With comprehensive training, retail staff can adequately discuss responsible sourcing issues with buyers, stimulate buyers’ interest in these issues, and help to shape their purchasing choices.

Industry associations, meanwhile, can support the creation of shared educational resources and training programmes on responsible sourcing, for commercial outlets. Individual customers, too, have a role to play, by ensuring that they research sourcing issues, retailers and their products in advance, and by making evidence-based ethical purchasing choices.

Through improved understanding of the social and environmental aspects of the coloured gemstone sector, from all those who participate in it at the retail level, the narrative of responsible sourcing can transcend the avoidance of negative issues and the fear of media, NGO and regulatory censure – leading to a robust and well-rounded responsible sourcing ecosystem, and to greater benefits for those in the supply chain who are most in need.